by Greg Piper

The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet” may not be as powerful as believed by the bipartisan chorus demanding reform of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

TikTok’s biggest immediate problem now may be its own users, their parents, and state attorneys general, rather than the state and federal lawmakers seeking to ban the Chinese-owned company and force ByteDance to sell it to an American entity, following a 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruling Aug. 27 that denies TikTok legal immunity for an algorithm choice.

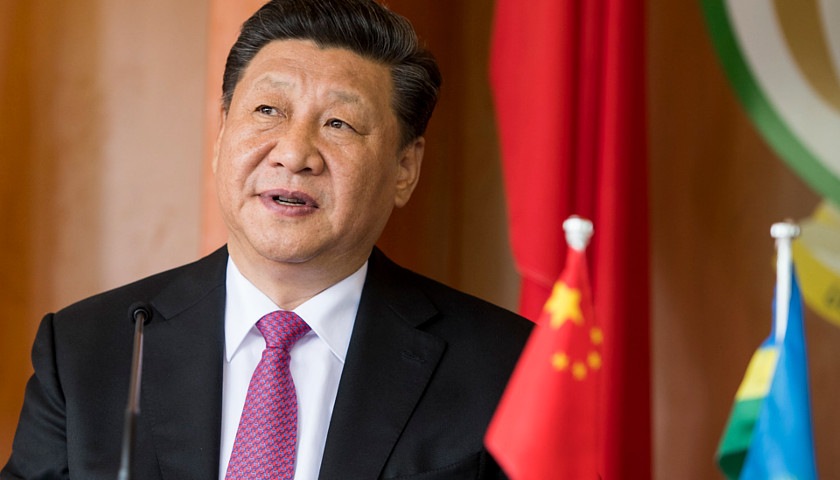

The potentially crippling liability a whole host of apps could now face is a civil parallel to France’s arrest and indictment of Telegram founder and Russian exile Pavel Durov, who faces up to 10 years in French prison for just one charge, for his hands-off approach to content moderation and resistance to governments.

Signal, Apple, and Meta’s WhatsApp are concerned by one of the charges – providing “cryptology services aimed at ensuring confidentiality without a license” – according to “three people with knowledge of the companies,” The New York Times reported Thursday.

That’s because they also provide end-to-end encrypted messaging but in a different way than Telegram, “putting them in a tricky position of whether to rally around their rival” as they often do with each other when governments challenge encryption, the Times said.

Was the Biden administration involved in the arrest of Telegram CEO Pavel Durov? Mike Benz explains.

(1:20) Who Was Involved in Pavel Durov’s Arrest?

(15:50) How Telegram Is Used by the CIA

(27:22) Domestic Policy Doesn’t Exist

(34:19) The Redefining of Democracy

(39:21) The… pic.twitter.com/cmgWWCIIpw— Tucker Carlson (@TuckerCarlson) August 28, 2024

By recommending and promoting videos including the “Blackout Challenge” to 10-year-old Nylah Anderson, who “unintentionally hanged herself” carrying it out, “TikTok’s algorithm … was TikTok’s own ‘expressive activity'” rather than the little girl’s, meaning Section 230 doesn’t bar her mother Tawainna Anderson’s claims, the Philadelphia-based 3rd Circuit ruled.

In a footnote likely prompting meetings between engineers and in-house counsel across Silicon Valley and other tech-heavy metros, the three-judge panel emphasized that TikTok’s recommendation to Nylah was “not contingent upon any specific user input.”

If the little girl had found the Blackout Challenge by searching TikTok, rather than through the platform’s “For You Page” uniquely curated to each user, “then TikTok may be viewed more like a repository of third-party content than an affirmative promoter,” the opinion said. (X, formerly Twitter, also has a “For You” curated feed for each user, distinct from their “Following” lists.)

Hence the panel is not addressing whether Section 230 “immunizes any information that may be communicated by the results of a user’s search of a platform’s content.”

American Economic Liberties Project Research Director Matt Stoller, an influential but polarizing progressive advocate for breaking the cozy relationship between Big Tech and Democrats, called the ruling “a bit of a shocking Holy S#@&! Moment” by ending “Section 230 as we know it” in an X post. “It’ll take a bit of time, but the business model of big tech is over.”

Free Press senior counsel Nora Benevidez wrote on X: “We’re sweeping the courts to reach accountability for bad actors and harmful behavior by platforms.” The progressive advocacy group organized the #StopToxicTwitter coalition after Elon Musk purchased the platform and took credit for “pushing half of the company’s top-100 advertisers to stop their spending.”

“Second order effect: content moderation cost goes up massively, AI steps in,” predicted Sundeep Peechu, general partner and founder of venture capital firm Felicis.

This ruling on Section 230 is huge. If it holds, TikTok/FB will be held accountable for harm from algorithmic feeds.

Second order effect: content moderation cost goes up massively, AI steps in. https://t.co/cAvoDnQkF9

— Sundeep Peechu (@speechu) August 29, 2024

The opinion was barely 10 pages long and about half was footnotes, including a lengthy acknowledgment that it “may be in tension” with six other circuits’ precedents and even its own.

The 3rd Circuit’s 2003 ruling that immunized another “interactive computer service” for failure to prevent “harmful online messages” between users, however, is legally distinct because it did not involve “recommendations via an algorithm,” President Obama nominee Judge Patty Shwartz wrote for the panel.

She emphasized all those rulings also predated this summer’s Supreme Court ruling in Moody v. NetChoice, a consolidated case remanded to trial courts to consider whether Florida and Texas laws that restrict how platforms can moderate content are “facially constitutional.”

The high court said algorithms that reflect “editorial judgments” about compiling third-party content are First Amendment-protected “expressive product[s],” Shwartz wrote.

Industry advocates blasted the ruling, with former Google associate general counsel Daphne Keller twice calling it “absurd” in an X thread. “How dare they create a circuit split and force an exhausted nation to go through this AGAIN.”

The 3rd Circuit is pretending SCOTUS “actually decided this issue” when the “whole point of 230 was to encourage and immunize moderation” including algorithm ranking, said Keller, now platform regulation director at the Stanford Cyber Policy Center. “There is NO CONFLICT.”

TechFreedom internet policy counsel Corbin Barthold, whose group fights internet regulation, said SCOTUS “had no effing idea what to do” when asked to withhold Section 230 protection for “up next” YouTube recommendations in last year’s case over terrorist ISIS videos.

Let's not forget that, the last time the SCOTUS justices were asked to draw an "algorithm" line for Section 230, they had no effing idea what to do.https://t.co/wbAmBAu0FY https://t.co/j51Fnkp0kW pic.twitter.com/W0dsKOL6GY

— Corbin K. Barthold (@corbinkbarthold) August 28, 2024

Judge Paul Matey, like third panel member Peter Phipps nominated by President Trump, pulled no punches in a lengthy and literary partial concurrence and dissent that sketched out the circumstances under which Section 230 was hastily slipped into a 1996 telecom overhaul.

The swashbuckling jurist blasted nearly three decades of jurisprudence on Section 230, “from the early days of dialup to the modern era of algorithms, advertising, and apps,” for conflating “free trade in ideas” with the “digital ‘cauldron of illicit loves’ that leap and boil with no oversight, no accountability, no remedy,” quoting Saint Augustine’s Confessions.

The law does not “permit casual indifference to the death of a ten-year-old girl” as claimed by “a host of purveyors of pornography, self-mutilation, and exploitation,” Matey wrote. The “nearly-limitless interpretation” is not based in Section 230’s words or context, “the history of common carriage regulations” or “centuries of tradition” on limited immunity for distributors.

The maximalist interpretation in the 4th Circuit’s 1997 Zeran ruling was “cut-and-paste copied by courts across the country” in the early years of the law despite criticism that it was “inconsistent with the text, context, and purpose” of Section 230, Matey wrote, citing Justice Clarence Thomas’s 2020 call for the high court to interpret the law in an “appropriate case.”

TikTok “may decide to curate the content it serves up to children to emphasize the lowest virtues, the basest tastes,” Matey wrote. “It may decline to use a common good to advance the common good. But it cannot claim immunity that Congress did not provide.”

– – –

Greg Piper is a reporter for Just the News.