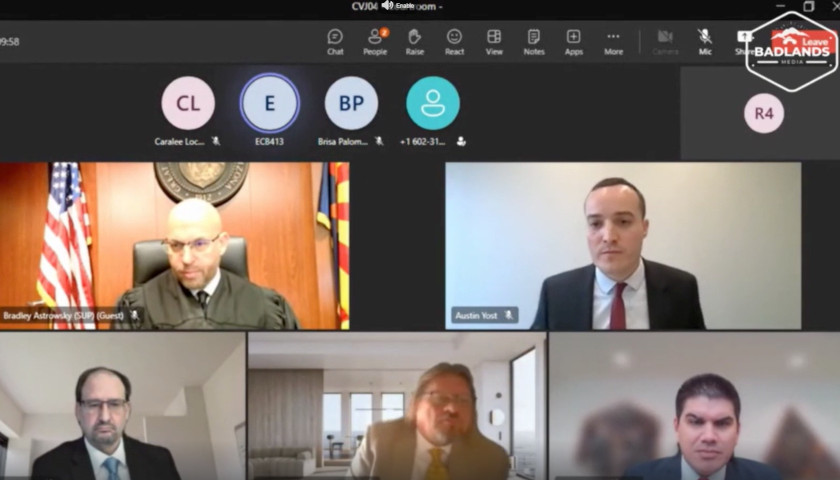

Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Brad Astrowsky conducted a hearing Wednesday regarding Maricopa County and Runbeck Election Systems’ motions to dismiss a lawsuit filed by We the People AZ Alliance (WPAA). WPAA requested video surveillance from Runbeck showing ballots being transferred to and from Runbeck on Election Day and the day after the 2022 general election. Runbeck refused to turn them over, claiming it was not subject to public records requests as a private entity, so WPAA sued the company.

Astrowsky began the hearing by stating that if there is a factual dispute, he may schedule a trial and discovery to get to the bottom of it before getting into the legal part of the motion to dismiss. He acknowledged that the court can consider matters outside of the pleadings, such as public records, noting that the contract between the county and Runbeck is a public record. He added that the county’s election policies are also public records.

WPAA’s attorney, Bryan Blehm, who is also representing Kari Lake in her election contest, responded and said there is a factual issue. He cited the testimony of Maricopa County Recorder Stephen Richer at Lake’s election contest trial in December when Richer said that the county doesn’t count the ballot affidavit packets that come into the county from the different vote centers and drop boxes on Election Day since “in essence there are too many of them.” Blehm said Richer admitted “they truck them over to Runbeck and use Runbeck’s equipment with their employees.”

Blehm added, “They make a big deal about the fact their employees are in charge those two days.”

He said the factual dispute is that Runbeck delivered over 292,000 ballots to the county, but the county said they sent only 270,000 ballots to Runbeck, something Richer tweeted. Richer told the Maricopa County Supervisors that he couldn’t reconcile the numbers, Blehm said. He also pointed out that Maricopa County Elections Co-Director Rey Valenzuela testified that he was in charge of early voting, which includes mail-in ballots that were delivered. Valenzuela said the county doesn’t count at its central tabulating site, MCTEC, as required by law, instead, they use Runbeck’s facilities to count the ballots. The law requires counting the ballots before they go to Runbeck.

Astrowsky said since that information wasn’t included in the lawsuit, he would not consider it, so there was no factual issue to decide. Blehm requested leave to amend the complaint and add it, and Astrowsky denied his request.

Astrowsky said there were two questions to consider when determining whether to grant the motions to dismiss. First, is Runbeck subject to public records requests? If not, then the case gets dismissed. If Runbeck is, the court must consider whether video surveillance falls into the items that must be turned over for those requests. If it does, then the case survives a motion to dismiss.

Astrowsky went over Runbeck’s role in the last election. He said Runbeck prints and assembles mail-in ballots, then gives them to the county, which mails them to voters. The ballots are mailed by voters back to the county, which turns them over to Runbeck. Runbeck scans the signatures on the outside of the envelopes, which go into a file reviewed by the county for signature verification. Meanwhile, Runbeck stores the ballots, and after signature verification is complete, Runbeck sorts the ballots into different categories and drives them to the county, which then conducts the counting. Runbeck never opens the envelopes containing the ballots, he added.

Joseph LaRue, the attorney for Maricopa County, said two controlling cases have addressed the issue, both by the Arizona Court of Appeals on whether Cyber Ninjas was subject to public records requests in its capacity overseeing the 2020 independent Maricopa County ballot audit for the Arizona Senate. The court found that it was and required Cyber Ninjas founder Doug Logan to turn over his personal communications. LaRue said the question regarding Maricopa County is “did they outsource an important government function to Runbeck?”

Although WPAA has stated it saw video surveillance at Runbeck, LaRue said, “Maricopa County doesn’t even know if a security tape exists, let alone be under their control.” He later testified that the county sends security to Runbeck to oversee the election processing.

LaRue said that while “opening and reviewing ballots” is an “important government function,” “counting ballot envelopes” is not.

Astrowsky pointed out how the Cyber Ninjas cases relied on Forum Publishing v. City of Fargo, which analyzed whether there was a delegation of a public duty. There, the court held that personal records of public employees are public records subject to public records requests.

Astrowsky said, “There’s no dispute that Runbeck was in charge — but where is the law drawn in terms of how much of that public function is delegated that makes a private entity or contract subject to it?”

He added, “Certainly running a general election is an important public function. If it was just printing the ballots, We the People AZ Alliance wouldn’t be here. They were in charge of assembling and getting out, then scanning the signatures. You can’t have an election without the role they played. So the issue is where is the line in an election case, and did what Runbeck do cross that line.”

LaRue shot back that Runbeck wasn’t conducting “election administration,”; it was providing “ministerial services that are important.” He said “it’s not an important governmental function,” and Runbeck merely “provides conveniences to the county.” LaRue compared Runbeck’s responsibilities to a printer.

Astrowsky said, “Administering the election involves ‘securing the security’ and ensuring the security and integrity of ballots that have been sent in. So isn’t tasking Runbeck with securing the ballots once they’ve been sent in, isn’t that administering the election? … That’s an important government function to maintain the integrity of the election.”

LaRue responded that interpreting it that way would subject the United States Postal Service (USPS) to the same requests since they also handle ballots through the mail. Astrowsky disagreed and said that “[s]ecuring the integrity of ballots prior to counting” differs from what USPS does.

Austin Yost, the attorney for Runbeck, emphasized in his arguments that for Runbeck to be subject to public records requests, the elections must be “entirely outsourced” to Runbeck, and it must be “in sole possession” of handling the elections. He said Runbeck’s duties were “not core governmental functions,” and the county retained control. On the other hand, he said the legislature delegating the election audit to Cyber Ninjas was a core governmental function.

Blehm retorted that it was a “misnomer” that the legislature outsourced everything to Cyber Ninjas since it retained all its essential legislative authority. He said the county couldn’t easily replace Runbeck in conducting elections, unlike replacing a janitor who provides restroom supplies like toilet paper to the county. He said the county couldn’t easily obtain “tens of thousands of different ballot styles from Staples and deliver them to the correct voters.” He went on, “What Runbeck does touches every voter in Maricopa County,” noting that 60 percent of the state lives in Maricopa County.

Blehm said although USPS isn’t subject to Arizona’s public records laws, it is subject to federal FOIA laws. He would submit a FOIA request if he wanted records about ballots from USPS. He said the defendants’ motions to dismiss are full of law that says there must be “substantial day-to-day control” for a private company to be subject to public records requests.

“We agree that there is substantial control by virtue of this contract,” he said. “Maricopa County has the power to tell Runbeck to fire person A; we don’t like person A. Maricopa County’s employees, as stated by Yost, are housed in this facility to oversee Runbeck’s election operations. Not a single voter in Maricopa County is unaffected by Runbeck.”

He continued, “Runbeck exists for the sole purpose of participating in our elections. They advertise it…. It’s concealing the truth — there’s a ballot in every envelope. It’s the most fundamental basic right in a constitutional republic, to elect their representatives. We’re not talking toilet paper or road construction.”

Astrowsky asked Yost, “If there is surveillance for security and integrity, doesn’t that make it subject to public records requests?”

Yost responded that there was no nexus between the video and the government’s activities.

“A video would have been taken regardless.” He said that WPAA admitted in their complaint that Runbeck put in the video surveillance in order to deal with threats. “Only the foggiest connection to the services Runbeck performed for the county,” he claimed.

However, later on, Yost contradicted himself, denying that the surveillance was related to Runbeck’s contract with the county for the election.

“Runbeck would have had security camera footage with or without the contract,” he said.

Yost said the “filming of loading and unloading trucks” isn’t part of “important governmental work.”

Astrowsky said, “Doesn’t the public have the right to know if they mail in a ballot and it’s being delivered to a private entity that’s going to handle it for awhile, that it’s being handled well, no haphazard baggage handlers at an airport … things get lost.”

LaRue responded and said that’s what chain of custody requirements are for, ignoring that WPAA wanted the video due to gaps in the chain of custody. He claimed that if Runbeck was subject to public records requests, it would “open up every church” that hosts voting sites for public records requests.

Blehm said the security video was a crucial part of operations since the county wouldn’t have hired Runbeck if they didn’t use it. He said he provided the court with evidence that Runbeck has surveillance video. Blehm said that evidence Runbeck’s role is more important than “just printing stuff” is what if a “fire broke out and destroyed ballots.” He added, “They’re not just unloading crates of toilet paper.”

Astrowsky concluded the hearing and said he would issue a written ruling shortly.

– – –

Rachel Alexander is a reporter at The Arizona Sun Times and The Star News Network. Follow Rachel on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].

Photo “Hearing” by Badlands Media.

22,000 extra ballots produced out of thin air. Nothing to see here says the courts. Move along!