At the Thursday evening meeting of the East Bank Stadium Committee, a council member praised an economist’s presentation about public investment in sports stadiums as more valuable than the paid report the council approved a company to do.

Professor of Economics, Finance and Quantitative Analysis at Kennesaw State University, J.C. Bradbury, delivered an information-dense presentation in rapid-fire fashion to the East Bank Stadium Committee (EBSC), of which Council Member Delishia Porterfield (District 29) was highly complimentary and appreciative, especially in comparison to the Vision Stadium Group (VSG) report that had a cost of at least $250,000.

“I’m really angry sitting here, because I feel like I got more from your presentation that you did for free, that we did not pay for, that you have no vested interest in than the presentation we actually paid a company to do,” said Porterfield.

Bradbury revealed on Twitter that, in response to a series of tweets from Council Member Zach Young (District 10) disparaging Bradbury and accusing him of receiving funding from and being a Trojan Horse for the Charles Koch Foundation, he spent 14 hours putting together the presentation for his EBSC appearance. He also drove the 200 miles to Nashville from Cobb County, Georgia on his own dime and time, and stayed at a relative’s house while in Music City.

“There have been many of that have been saying from the beginning of this, you know, we want to be able to make an apples-to-apples comparison. Give us the facts. Give us the data, so that we can make a decision that’s the most fiscally responsible for the people of Nashville,” Porterfield implied about the information that has not been received from the administration but Bradbury provided.

Bradbury has authored two books on the economics of baseball, The Baseball Economist and Hot Steve Economics, in addition to a number of articles on the public and sports economics. He is an associate editor for the Journal of Sports Economics and president-elect of the North American Association of Sports Economists.

Economists have “consistently found no substantial evidence of increased jobs, incomes, or tax revenues” associated with stadiums, arenas, sports franchises and sports megaevents, Bradbury indicated in his first slide about the proposed stadium project, and that “the level of venue subsidies typically provided far exceeds any observed economic benefits.”

University of Chicago’s survey of economic experts are confident in these conclusions by a large majority – 57 percent agreeing and 26 strongly agreeing.

Bradbury says that the unrealized economic benefits is due to spending at sports events being reallocated from other local spending, but not new economic activity that generates additional tax revenue.

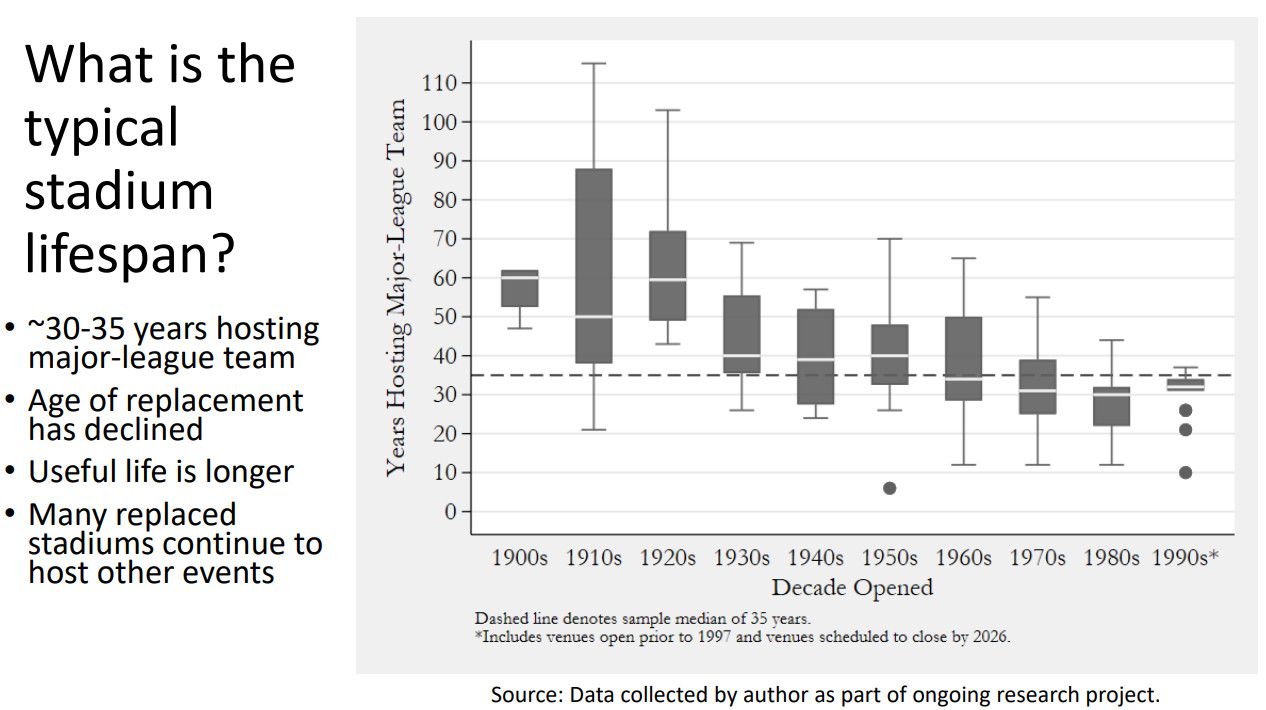

Bradbury then dug into more specifics about sports stadiums. Based on research he had done for an ongoing project, Bradbury found that the typical stadium lifespan is approximately 30 to 35 years. However, the replacement age has declined so that new stadiums are replaced with useful life remaining and stadiums that are not demolished continue to host other events.

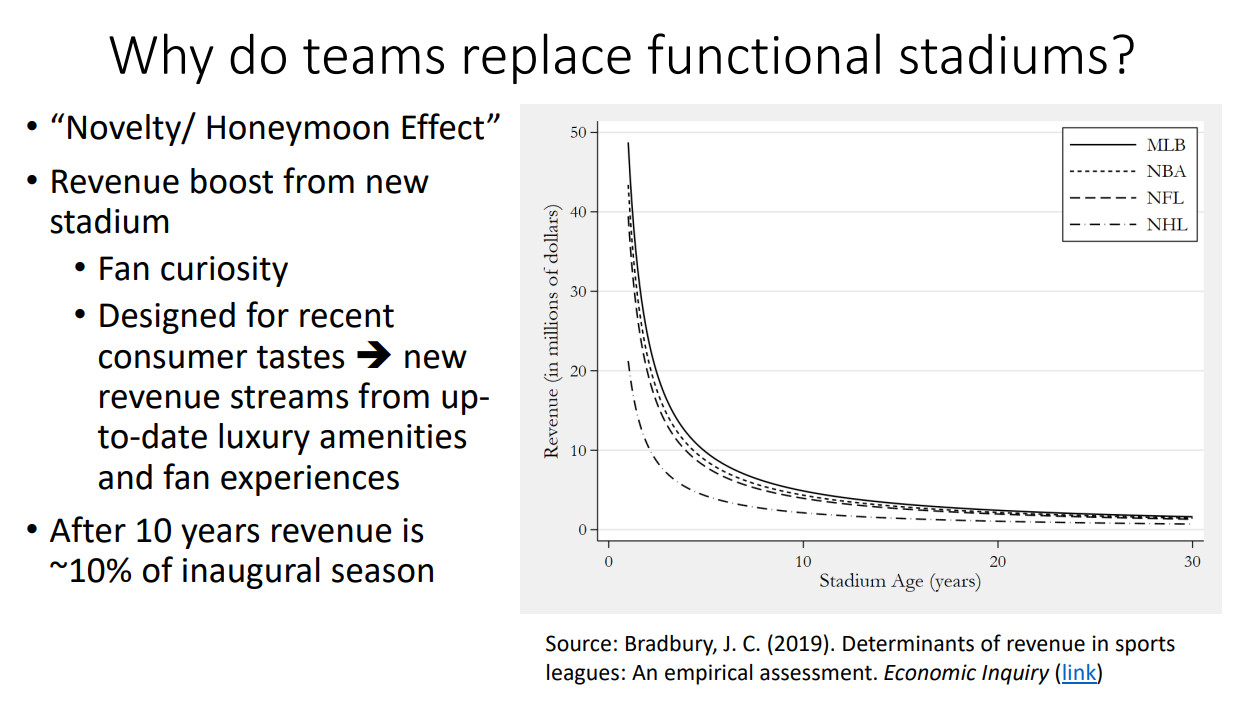

Teams replace functional stadiums, according to Bradbury, once the novelty wears off. In evidence of this, Bradbury had a slide that showed that after about 10 years, stadium revenue is about 10 percent of its inaugural season for the MLB, NFL, NHL and NFL alike.

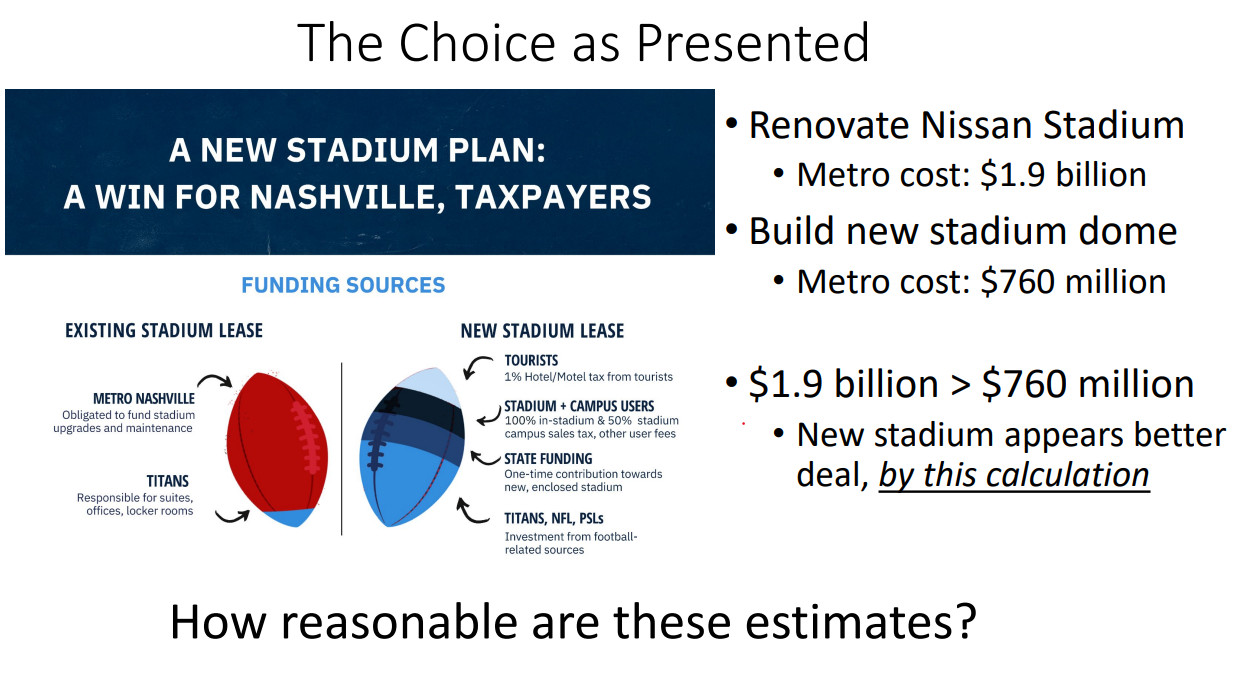

Using the graphics provided by the Tennessee Titans comparing the existing stadium lease to the new one, Bradbury said the new stadium appears to be a better deal, emphasizing the qualifier of “this calculation.”

The “calculation” Bradbury refers to is Metro’s cost to renovate of Nissan Stadium of $1.9 billion versus a new stadium at $760 million. But, Bradbury goes on to question the reasonableness of the cost estimates for the two options.

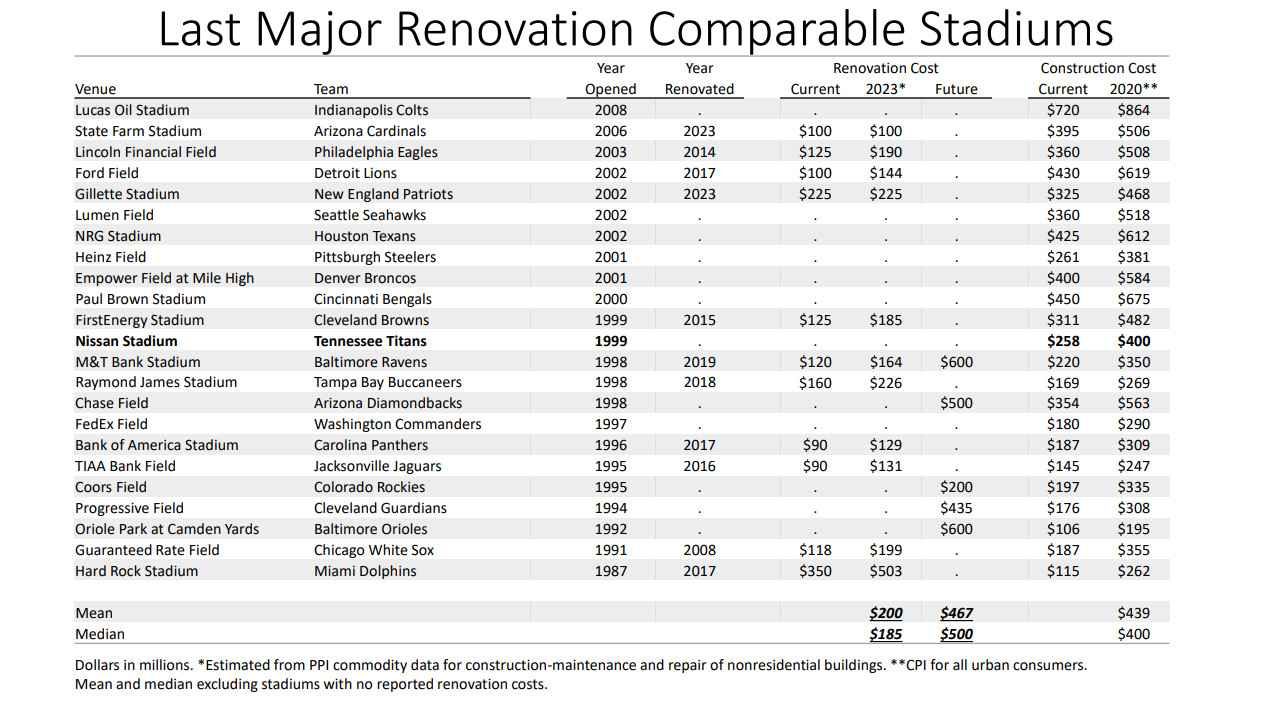

The sticking point with the current lease is the “first class condition” requirement at the “comparable facilities” specifically named as well as those referenced as being of similar age, meaning that they completed within 10 years before or after Nissan Stadium.

Bradbury lists 24 comparable venues that includes 24 NFL stadiums, 5 MLB stadiums that are still active and 2 MLB stadiums that have been replaced.

He then detailed the construction and renovation costs and dates for 24 comparable stadiums. Bradbury built in a conversion from the cost at the time of the expenditure to the projected cost. Bradbury’s “generous” inflation factor of 14 percent from 2022 to 2023, mimics that of 2021 to 2022, even though he believes it will be lower due to measures taken by the Federal Reserve.

Of the 11 stadiums that fit the “comparable stadium” criteria and underwent major renovations qualified as over $100 million, the average cost in 2023 dollars was $200 million. Those stadiums with planned renovations have an average cost of $467 million. Meanwhile, 7 of the comparable stadiums have had no major renovations.

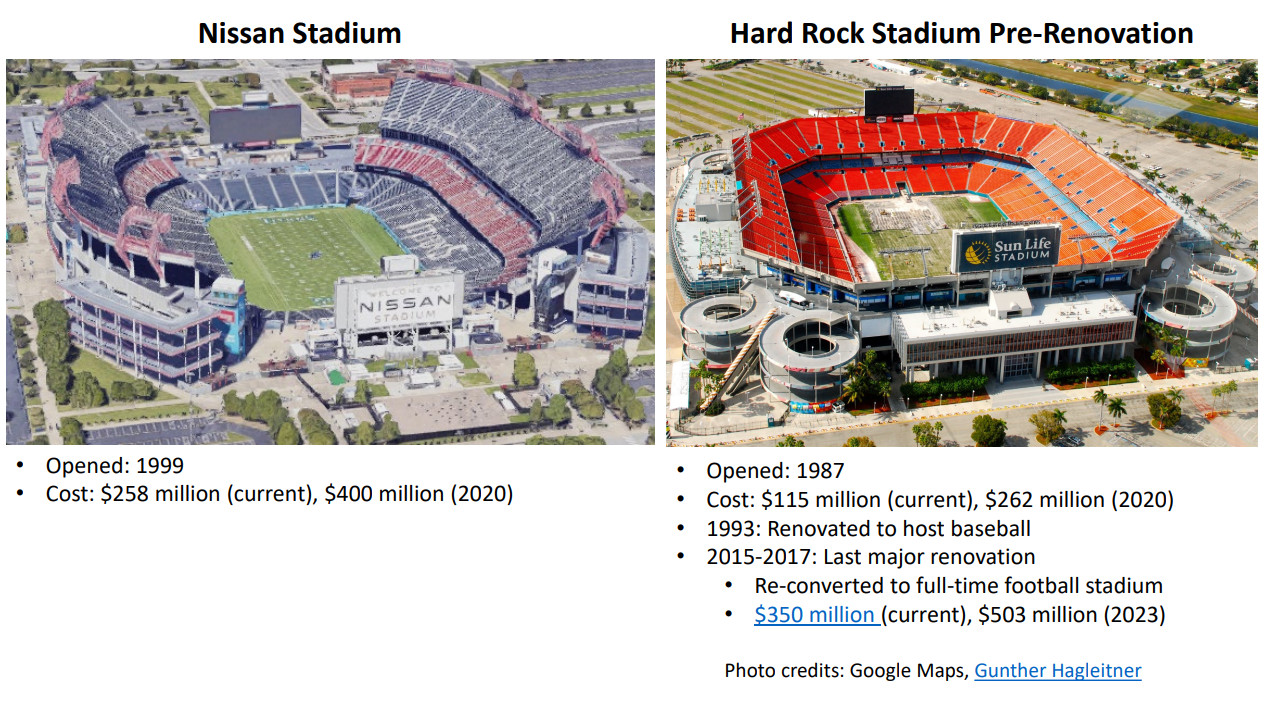

While VSG said, “In their professional opinion, Hard Rock Stadium [Miami, Florida] is the closest NFL comparative example with which to test against the proposed components of the Titans’ master plan,” Bradbury disagrees.

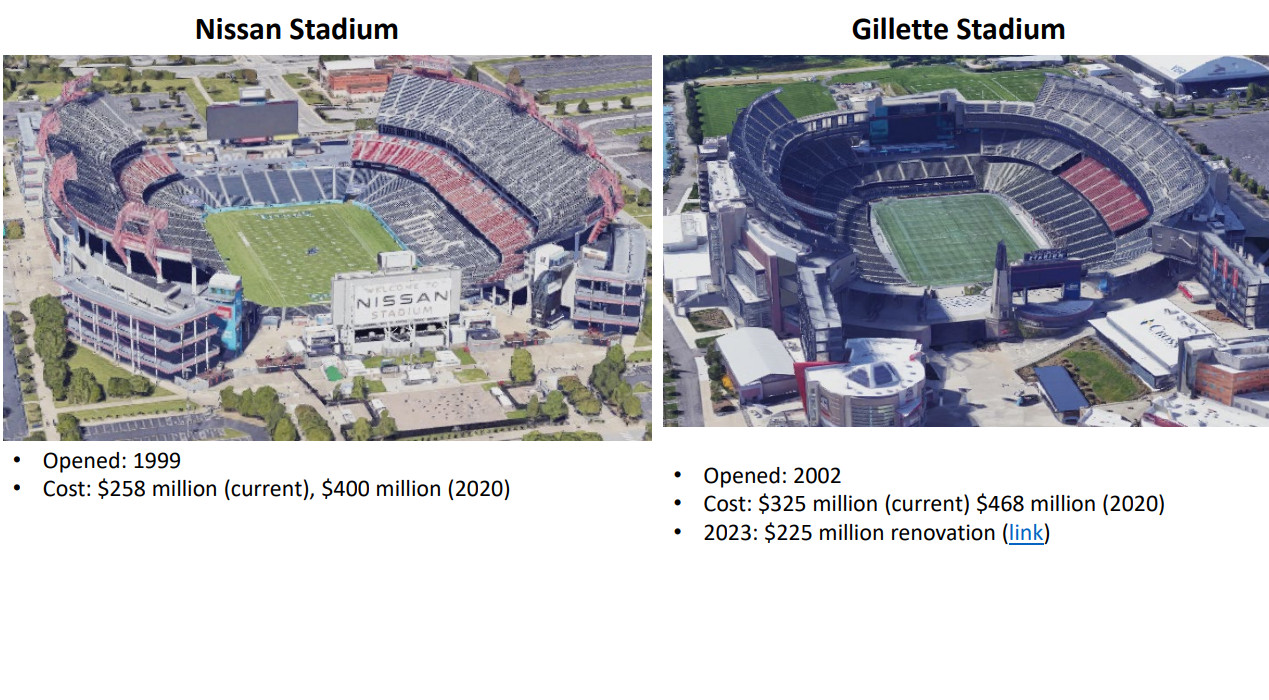

He said that if he were to pick one stadium, which he does not think is a good idea, he would pick Gillette Stadium. A “comparable stadium” built for the New England Patriots in 2002, it is currently undergoing a $225 million renovation.

To effectively make his point, Bradbury had overhead pictures comparing Nissan Stadium to both the Hard Rock and Gillette stadiums.

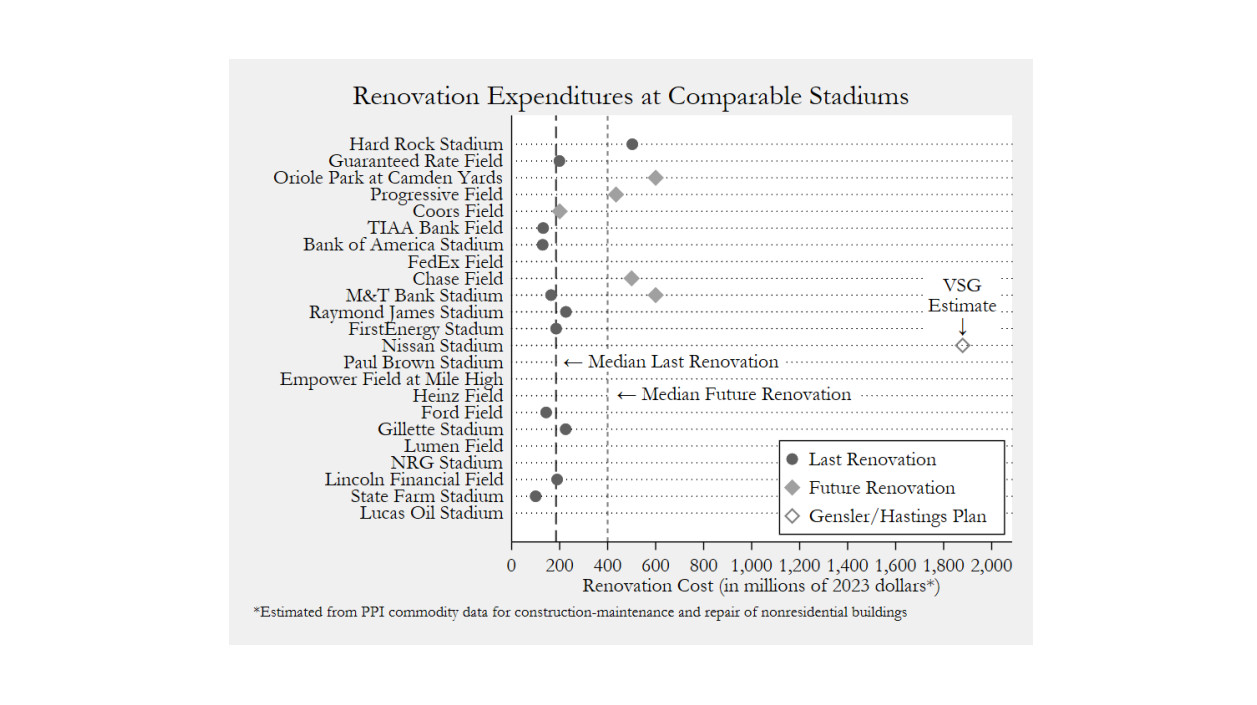

Bradbury then went on to compare the existing Nissan Stadium to the Gensler/Hastings proposed renovation, which VSG used as a “reasonable basis for what would be required in a plan that meets that [first class] standard.”

In one of his most illuminating slides, Bradbury charts the renovation expenditures at comparable stadiums. But, when the VSG estimate for the Gensler/Hastings renovation is factored in, Bradbury had to change the scale of the chart in order for it to fit into the chart area.

Council Member At Large and EBSC Chair Bob Mendes shared via Twitter some of the amenities that are included in the Gensler/Hastings plan the Titans recently released in its entirety and VSG estimated at a cost of $1.879 billion excluding the $235 million for post-renovation capital expenses between 2027 and the end of the lease term in 2039.

Upon further review, the Titans have provided the East Bank Stadium Committee with another more detailed document that they gave to VSG. This is the design document on which the claimed $1.8 billion Nissan renovation cost is based. It's posted here:https://t.co/NZXiqjmZlr https://t.co/7htdA6rMXe

— Bob Mendes (@mendesbob) November 15, 2022

Bradbury also said he could find no public record that indicated the Hard Rock renovation cost is as high as the $550 million VSG reported, although he did cite a reference to a $350 million cost.

Bradbury’s conclusion on the renovation cost estimate is that the $1.879 billion estimate far exceeds the $200 million at comparable facilities and the Gensler/Hastings plan is not a reasonable basis for required improvements at Nissan Stadium.

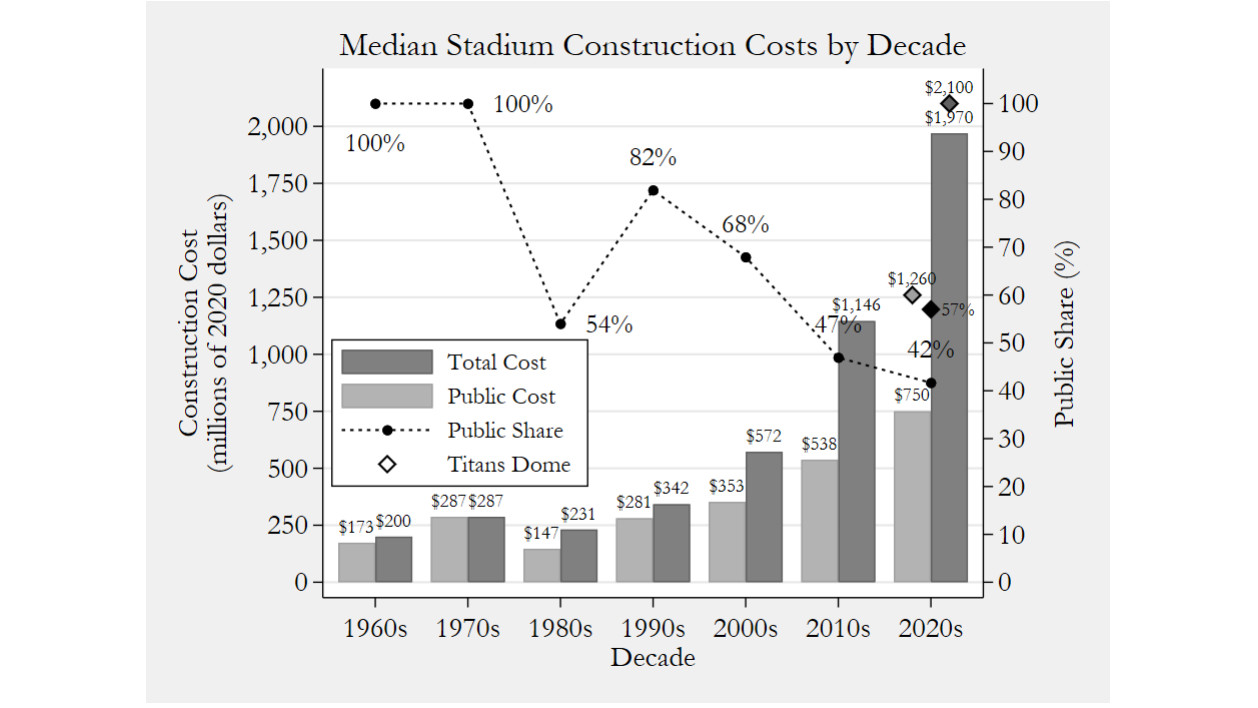

In looking at the proposed new domed stadium, Bradbury points out that the public contribution of $1.26 billion – with $500 million coming from the state and $760 million from Metro – of the $2.1 billion total cost represents 57 percent.

In another revealing slide, Bradbury maps the median stadium construction costs by decade along with the cost to the public in terms of both dollars and percent. Over the past 60 years, the public’s share has increased in terms of dollars, but has decreased as a percentage of the total cost.

With the public share including both state and local dollars being 57 percent of the new Titans Stadium, it far exceeds the current average of 42 percent public contribution.

Bradbury also shed light on the funding mechanisms made available to Metro by state legislation.

The additional hotel tax, Bradbury says, is not a windfall gain, in that the dome may add some new hotel stays, but that will be limited and such events have also displace existing visitors.

He put the additional hotel tax revenue from a major event into perspective by using the 2017 Super Bowl held in Houston, Texas as an example. With the total increase in hotel revenue of $44 million dollars, the additional one percent increase in the hotel tax would result in $440,000 tax revenue.

Additionally, hotel taxes are not just paid by tourists and the price of a room is a negotiation between the seller and the buyer. If the price as perceived as too high by the buyer, the hotel will have to lower the room price, which also lowers tax revenues. Bradbury said this is a very complex evaluation, and one that has yet to be done.

Bradbury also argues that the second source of revenue in the way of sales tax collected from the Campus surrounding the stadium is also not new revenue. Rather, spending in the East Bank development will come mostly from other areas in the city. As a result, spending diverted to the stadium area will result in tax revenues being diverted away from the general fund and other public needs and services and to the funding of the stadium.

In other words, says Bradbury, there is “no free lunch.”

Bradbury adds a variety of points about the stadium funding mechanism relying on the speculative development of the East Bank, but overall deems it a “poor strategy.”

Not only has Bradbury studied and written about public spending on stadiums, he lives within 10 miles of Truist Park in Cobb County, Georgia. The new home of the Atlanta Braves came at a cost of $300 million from Cobb County taxpayers to lure the team from downtown Atlanta’s Turner Field built just 17 years prior, Bradbury reported in Reason.

Similar to Mayor John Cooper’s vision for the East Bank, Truist Park is surrounded by $400 million mixed-use development with the entire campus known as “The Battery.” Unlike Cooper’s East Bank development, however, the The Battery is privately owned and operated by the baseball club.

Bradbury concludes in his “Comprehensive Report on the Economic Impact of Truist Park and The Battery Atlanta on Cobb County” that, “[T]he evidence does not support the widespread claim that the $300 million invested by the County to fund the stadium was a sound financial investment. Available financial figures demonstrate that the stadium runs significant annual deficits, which will likely continue for the remaining 25 years of the County’s commitment.”

This, coming from someone who also said he is “a life-long Atlanta Braves fan with deep roots in Cobb County” for whom “bringing major-league caliber baseball to Cobb County is certainly desirable to baseball fans (like myself)” in the same report.

Positing a unique perspective, Bradbury said that the cost to Metro taxpayers is actually $810 million, when their 10 percent of the state’s $500 million contribution is added to the Metro’s direct contribution of $760 million.

Additionally, Metro taxpayers will have to fund their contribution of the $450 million being requested for other stadiums in the state. That share will be added to the still unknown amounts for the Campus development costs, costs for at least 2,000 parking space and funding for the capital repairs reserve fund.

Bradbury cautioned against the “fiscal illusion” that Metro’s burden is funded only by visitors.

“Funding comes from [the] existing tax base, no matter the tax instrument,” said Bradbury.

From a survey of more than 130 studies spanning 30 years, Bradbury and two colleagues found, “[T]he large subsidies commonly devoted to constructing professional sports venues are not justified as worthwhile public investments.”

As his final slide, Bradbury cautioned against the siren call common to publicly-funded stadiums that “[T]his one will be different.”

The video of the East Bank Stadium Committee of Thursday, November 17 can be watched here. Due to equipment failure, some portions of the meeting are unavailable.

– – –

Laura Baigert is a senior reporter at The Star News Network, where she covers stories for The Tennessee Star.

Photo “J.C. Bradbury” by Kennesaw State University. Background Photo “Nissan Stadium” by Nissan Stadium.

Who would have thought a study paid for by the council was more about what the authors thought the council wanted to hear than about objective analysis?