by Robert Romano

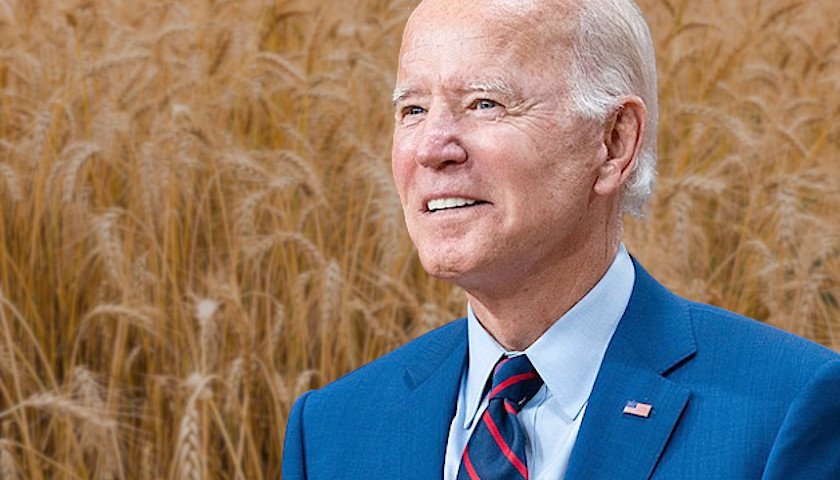

President Joe Biden is promising to boost U.S. production of wheat to offset the loss of Ukrainian and Russian exports from the Black Sea thanks to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that has shut down the ports there, stating at a farm in Illinois on May 11 that he would extend crop insurance for farmers who double crop in a bid to get more wheat to market this year.

Already, the global shortfall is 4.5 million tons this year, so far, according to the latest data by the Department of Agriculture: “Global production is forecast at 774.8 million tons, 4.5 million lower than in 2021/22. Reduced production in Ukraine, Australia, and Morocco is only partly offset by increases in Canada, Russia, and the United States. Production in Ukraine is forecast at 21.5 million tons in 2022/23, 11.5 million lower than 2021/22 due to the ongoing war.

Biden warned that Ukraine cannot move its current winter wheat crop out to markets, consisting of 20 million tons, without which could trigger starvation in the third world: “Ukraine says they have 20 million tons of grain in their silos right now — 20 million tons. And guess what? If those tons don’t get to market, an awful lot of people in Africa are going to starve to death because they are the sole — sole supplier of a number of African countries.”

The problem is Russia’s blockade of Ukraine’s ports, Biden said: “[B]ecause of what the Russians are doing in the Black Sea, Putin has warships — battleships preventing the access to Ukrainian ports to get this — this grain out, to get this wheat out. The brutal war launched on Ukrainian soil has prevented Ukrainian farmers from planting next year’s crop and next year’s harvest.”

Meaning the shortfalls will conceivably last as long as the war in Ukraine lasts. The problem is that the war in Ukraine has been going on since 2014 after former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was removed from power as Russia annexed Crimea and the war in the eastern Donbass region began. Now with both sides digging in for more fighting, a stalemate appears to be worst possible outcome.

But will Biden’s plan even work? U.S. wheat production is down 15 percent since 2019, from 1.93 billion bushels in 2019 to 1.64 billion in 2021, according to data compiled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Overall, the U.S. produces a little more than half of what it did in 1981, when it produced more than 75 million metric tons. That was down to 44.8 million in 2021.

The domestic wheat shortfall last year was thanks to major drought conditions that severely impacted production in Idaho, Montana and North Dakota, another hit to global food production that could not come at a worse time.

The biggest part of the problem is not enough has been planted. According to a March Department of Agriculture release on prospective plantings, 2022 will be the fifth lowest area planted since 1919: “All wheat planted area for 2022 is estimated at 47.4 million acres, up 1 percent from 2021. If realized, this represents the fifth lowest all wheat planted area since records began in 1919.”

Is Biden’s crop insurance program enough to avert potential starvation in the third world and beyond?

Given current conditions — Biden also complained in his speech that the spring had been very cool this year and that there was less time to plant more wheat this year — it appears unlikely the U.S. will be able to boost production to even get back to 2019 levels, let alone to offset drops in Ukrainian and Russian exports. Meaning, the worst may be yet to come.

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.