by Auguste Meyrat

Last week in the Atlantic, David Graham took aim at smart conservative politicians who play dumb. He declares at the beginning of his piece, “This is the age of smart politicians pretending to be stupid.” As evidence, he mainly cites Gov. Ron DeSantis, senatorial candidates J.D. Vance and Eric Greitens, and Sen. Josh Hawley.

Graham argues that these men belie their impressive degrees from Ivy League universities by aligning themselves with the populist conservative movement in some capacity. DeSantis does not brag about COVID booster shots, Vance is critical of China and globalism, and Greitens and Hawley have doubts about the 2020 election. Surely, according to Graham, these must be poses to win over Trump supporters, not sincere positions stemming from valid objections. There’s just no way such educated people would actually believe what they’re pushing.

It’s ironic that Graham’s essay on the behavior of intelligent people is remarkably stupid. The logic is sloppy and the purpose of the essay is juvenile. Unfortunately, this mode of thinking has become representative of many leftists, so it’s worth our time to dismantle it and judge it accordingly.

The main logical fallacy of this essay is begging the question — forming conclusions on unproven assumptions. By associating all conservative populist positions with falsehood, Graham assumes that all popular positions among today’s conservatives are necessarily ignorant. But this begs a few questions: Is it wrong to be skeptical of the effectiveness of COVID booster shots? Is it wrong to point out the tradeoffs of globalization? Has it been proven wrong that the last presidential election wasn’t riddled with problems?

No, these are still debated issues, and the facts will often support the conservative position more than the progressive one. This doesn’t seem to matter to Graham, who goes on to conclude that these politicians are playacting to win votes among the troglodyte Trumpkins.

Another fallacy that Graham commits is equivocation — applying different meanings to a key term. In Graham’s essay, the equivocated term is “smart.” In one case, he seems to appreciate that attending an Ivy League university doesn’t always equate to being smart: “Of course attending fancy schools does not necessarily make someone smart, nor do the well educated have a monopoly on intelligence.” For the rest of the essay, however, he proceeds to use formal education as shorthand for a person’s intelligence.

This inevitably leads to yet another fallacy of circular reasoning — supporting one claim by offering a definition rather than proof, thereby going in a circle. Graham does this twice. First, he claims that populist conservatives are dumb because they believe in certain claims of conservative populism. Why do they believe in these claims of populist conservatism? Because they’re dumb. Why are they dumb? Because they believe in the claims of populist conservatism.

Similarly, he asserts that Ivy League graduates are smart because they graduated from an Ivy League school. Why did they graduate from an Ivy League school? Because they’re smart. Why are they smart? Because they went to an Ivy League school.

Somehow, Graham is able stretch out this childish reasoning for more than 1600 words (for reference, this essay’s under 1000). And all for what? To slam a few popular conservatives and characterize their supporters as anti-intellectual. Put simply, a leftist writer is calling those on the right idiots so that he can claim the intellectual high ground.

If it were only one writer, this really wouldn’t mean much, but this is a common belief among leftists. Bill Maher has built his comedy by smugly lambasting conservatives and Trump supporters as hateful idiots. Last year, Politico devoted a whole essay to Democrats struggling with being too educated — this was part of their “Big Idea” essay series, no less. Even President Biden recently thought it’d be appropriate to call a Fox News reporter “a stupid son of a b*tch.” Given that Biden simply stood and smiled at his podium after this comment, this was likely more a moment of honesty (or senility) than a slip of the tongue.

Why is this? As Graham demonstrates in his Atlantic piece, most leftists are prone to conflate intelligence with conformity to certain narratives. This is really what a college degree, particularly from a prestigious university, signifies. Young people go to learn their script, adopt the right positions, and judge those who don’t do any of this. As such, it is more accurate to say that college students are conditioned (taught what to think) than truly educated (taught how to think).

As for the actual indicators of intelligence — critical thinking, problem solving, analysis, logic — these actions are often discouraged, usually through social pressure or outright censorship. This can be seen in the ridiculous attacks on Joe Rogan who, though a self-proclaimed pothead and meathead, is himself far smarter than most media personalities. Moreover, his willingness to question and learn from others influences his listeners to become smarter themselves.

As much as the Left’s anti-intellectualism (what else can one call it?) hurts conservatives, however, it hurts the Left even more. Because they define intelligence and argue about it so superficially, they end up with embarrassingly ignorant and incompetent leadership. They elect leaders like Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, both of whom struggle mightily with articulating a single clear thought. They appoint justices like Sonya Sotomayor, who fails to understand the basic facts about a virus that has deeply impacted the country for over two years. They continue to worship experts like perpetually wrong Anthony Fauci.

Contrary to Graham’s claims, it seems that leftists are the one struggling with dumb leaders — except their leaders don’t seem to be pretending. Even if mocking conservatives makes him feel better about this sad truth, he and the rest of writers at the Atlantic would do better to take a step back, consider their arguments, and offer constructive solutions.

In other words, they can use their brains and be “smart” for once.

– – –

Auguste Meyrat is an English teacher in North Texas; a regular contributor to The American Spectator, The Federalist, the American Conservative, Crisis, and American Greatness; and the senior editor of The Everyman.

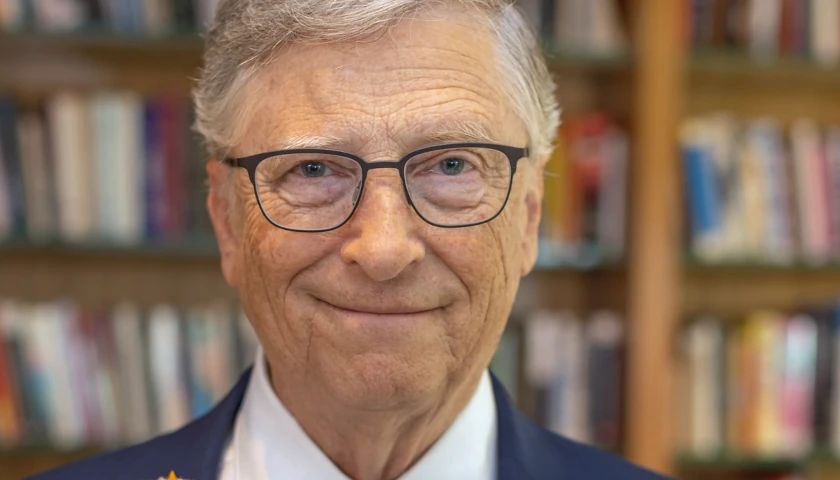

Photo “J.D. Vance” by Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 2.0.