by Andrew Busch

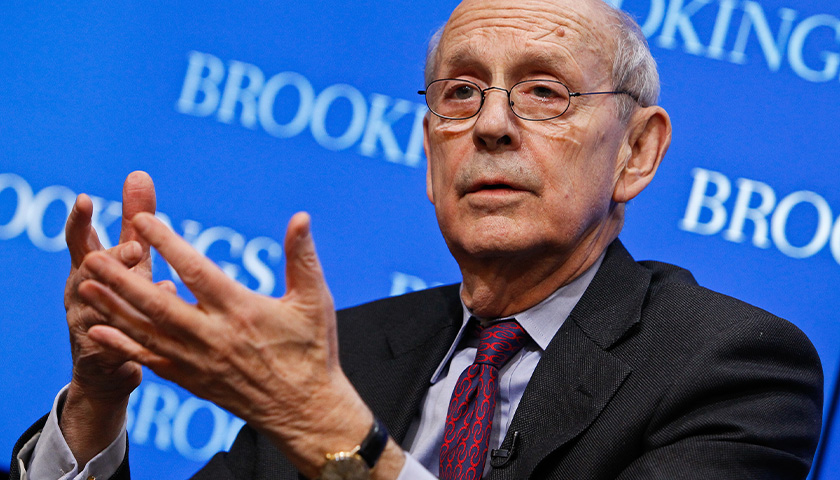

Wednesday’s announcement by Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer that he would be retiring at the end of the court’s current session has raised the obvious question of how contentious the battle over his replacement will be.

One thing is almost certain to be true: No matter who is nominated by President Joe Biden, there will be no 87-9 favorable vote – the tally when Breyer was nominated by Bill Clinton in 1994. Though there were occasional exceptions in the decade prior to Breyer, his vote totals were not unusual in that era. Antonin Scalia was approved 98-0, Anthony Kennedy 97-0, and Ruther Bader Ginsburg 96-3. However, no Supreme Court nomination since Breyer’s has received fewer than 22 negative votes, the number against Chief Justice John Roberts in 2005.

That was the year Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer (now majority leader) urged that senators should vote explicitly on the basis of candidates’ ideology rather than simply their qualifications. In reality, ideology had been the primary driving factor behind the rejection of Robert Bork’s nomination in 1987 and the tough, though ultimately successful, fight over Clarence Thomas’ nomination in 1991, but most opposing senators had attempted to preserve the fiction that judicial temperament or scandals were behind their “no” votes. Schumer opened the door to unabashed ideological and partisan warfare, and subsequent votes on Supreme Court nominations have shown it.

Since Roberts’ confirmation, there have been 42 votes against Samuel Alito, 31 and 37 against justices Sotomayor and Kagan, 45 against Neil Gorsuch, and 48 against both Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. This does not count the case of Merrick Garland, whose nomination was entirely stymied. It is highly likely in the current atmosphere that the next nominee will wind up with a closely divided, nearly party-line vote.

However, there are close votes, and then there are deeply contentious confirmation fights. Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito had the same number of negative votes, but Thomas’ confirmation fight was much more bitter. Likewise, Kavanaugh and Barrett both had 48 votes against them at the end of the day, but Barrett moved through her confirmation process with an ease Kavanaugh had to envy.

There are a few metrics that analysts will be tempted to use to predict how contentious the fight might become, but none of them are very satisfactory.

Perhaps, some might say, the fact that this is an election year will crank up the contention. There is a logic to this, insofar as senators will be looking to score political points and may be less likely to smooth the way for a nominee. However, many will also be looking to strengthen their personal reelection prospects or to advance their party’s chance of maintaining or attaining a majority. How the confirmation debate will fit into those goals will depend on who Biden nominates and how the public reacts. Kavanaugh and Barrett were both nominated in an election year, as was Garland. But Bork and Thomas were not.

The argument might also be made that this nomination will be less contentious than some others because Biden, a Democrat, will be nominating a replacement for Breyer, who was also the nominee of a Democratic president and one who has hewed pretty consistently to a liberal line. In defense of this proposition, one can point to particularly bitter fights over Bork, who was perceived to represent a shift to the right from his swing-vote predecessor; Thomas, who replaced liberal stalwart Thurgood Marshall; and Kavanaugh, who was appointed to replace swing-vote Kennedy. Garland’s nomination was tanked because a Republican Senate was unwilling to replace the conservative Scalia with an Obama appointee, especially so close to a presidential election.

However, here, too, there are counterexamples. Barrett, who was perceived to be a strong conservative, was nominated to replace feminist heroine Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The vote was very close, but the temperature was significantly lower than in some other cases. For her part, Ginsburg, with her 96-3 confirmation, shifted the court significantly to the left by replacing Byron White, a Kennedy appointee but one who had dissented in Roe v. Wade and otherwise frequently took a conservative stance.

Others might suggest that the age of the nominee makes a difference. The younger the nominee, the longer he or she will be on the bench if confirmed; the longer his or her projected tenure, the higher the stakes. At the time, some pointed to Clarence Thomas’ young age as an explanation for the harsh campaign that ultimately developed against him. But Bork and Garland, the two nominees who were actually stopped by the Senate, were quite a bit older than Thomas.

So how can we tell if Biden’s Supreme Court nomination is going to provoke a bitter fight, as opposed to just a close vote, which is likely in any case? The short answer is that it may not be possible to predict at this point. There are no hard and fast rules. It will depend on the strengths and weaknesses of the candidate, and on how quickly Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema pledge their votes to the nominee. If they are locked in early, Republican opposition may become pro-forma, even if it is unanimous or nearly unanimous. If either senator lingers, though, the opposition may smell blood in the water, and the confirmation battle could get ugly. The one thing none of the confirmation battles of the last three decades have had? A 50-50 Senate.

– – –

Andrew E. Busch is Crown professor of government and George R. Roberts fellow at Claremont McKenna College. He is co-author of “Divided We Stand: The 2020 Elections and American Politics” (Rowman & Littlefield).

Photo “Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer” by Brookings Institution CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.