by Peter Berkowitz

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

One might quarrel with Sun Tzu’s numbers in this famous formulation from the approximately 2,500-year-old Chinese classic “The Art of War.” But Western authorities on war starting with Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Clausewitz agree with Sun Tzu that knowledge of one’s strengths and weaknesses and knowledge of the enemy’s strengths and weaknesses are essential to sound strategy.

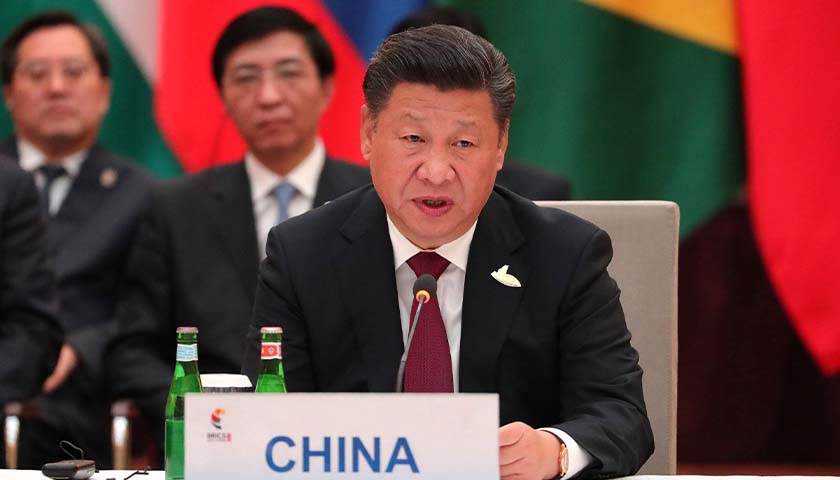

The same applies to strategy concerning countries called, in contemporary parlance, “rivals” or “strategic competitors.” Accordingly, as the United States gears up to confront the China challenge, we would do well to improve both our self-knowledge, which encompasses America’s free and democratic form of government as well as the nation’s diverse population, and our knowledge of the People’s Republic of China, which requires careful attention to the Chinese Communist Party’s conduct and thinking along with the interests and beliefs of the 1.4 billion people over whom it exercises repressive, one-party rule.

According to Elbridge Colby, the single most important fact about China today is that it is a great power that seeks regional hegemony in Asia, the globe’s fastest-growing economic region and home to more than half of the world’s population. And the most important fact about the United States, Colby contends, is America’s interest in blocking China from dominating Asia. Because the CCP has identified reunification by 2049 with free and democratic Taiwan—through whatever means necessary—as a central strategic objective and because such a conquest would consolidate Chinese hegemony in the Indo-Pacific, Colby’s lucid, painstakingly argued book, “The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict,” is essential reading. Because Colby does not pursue the implications of the fact that China is an authoritarian great power rooted in Marxism-Leninism and Chinese nationalism while the United States is a great power grounded in freedom and democracy, his analysis must be supplemented by a wider appreciation of the China challenge.

A deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategy and force development from 2017 through 2018, Colby recognizes the dependence of defense strategy on grand strategy—the comprehensive thinking about a nation’s interests, principles, and circumstances that links its short-term actions in foreign affairs to its larger purposes. However, he concentrates on elaborating a defense strategy that will enable Americans “at levels of risk and cost they can realistically and justifiably bear” to check China’s hegemonic ambitions within the Indo-Pacific. “Success for the strategy in this book would be,” he states, “a situation in which the threat of war is not salient.”

The end of “the uni-polar moment,” according to Colby, has heightened the salience of war. China today possesses the world’s largest population; its second largest economy; and a world-class military that includes the world’s largest navy, along with formidable nuclear, cyber, and aerospace capabilities. Beijing’s achievement of great-power status ended the “global preeminence” that the United States enjoyed following the Soviet Union’s 1991 dissolution. Foreign-policy experts who still consider the United States the lone superpower as well as those who think Washington must significantly cut back engagement with the world, Colby warns, neglect this substantial change in circumstances at America’s peril.

America’s surpassing interest in securing its own freedom does not entail, Colby stresses, that the United States must transform China into a liberal democracy or itself achieve hegemony in the Indo-Pacific. Nor does it mean, one should add, that the United States lacks an interest in the growth of freedom and democracy around the world or in the healthy operation of international institutions grounded in respect for national sovereignty and human rights. It does require, Colby insists, that the United States deny China’s achievement of hegemony in Asia.

Since the international realm lacks a supreme authority—notwithstanding the aspirations of U.N. diplomats and proponents of transnational governance—the United States must assemble a favorable balance of power in the region, Colby argues. Heightening the urgency is the CCP’s steadfast and brazen defiance of international law and norms, from the party’s internal oppression of Uyghurs (which, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo determined, rose to crimes against humanity and genocide), Tibetans, ethnic Mongolians, and Christians, to the use of its enormous economic clout to silence critics in corporate America and on campuses. While maintaining a balance of power involves sophisticated diplomacy and economic strength, the military component remains essential because physical force possesses, as Colby tactfully puts it, “unique coercive efficacy.”

To build an effective and sustainable balance of power in Asia, he counsels, the United States must reconfigure its alliance system. Reconfigure, he emphasizes, does not mean enfeeble or abandon. To the contrary, reconfiguring the U.S. alliance system in response to the China challenge calls for reinvigorating relations with allies and partners around the world and for sharing responsibilities more prudently with them. For example, as it shifts resources to deny China’s quest to control the rest of Asia, the United States must rely more heavily on European allies to protect Europe’s eastern flank. At the same time, the U.S. must enhance cooperation with fellow Quad members Japan, India, and Australia as well as with other nations in the region—including Taiwan, South Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia—that share America’s interest in preventing China from establishing an illiberal and anti-democratic Indo-Pacific order.

The CCP’s best option for gaining regional preeminence, according to Colby, is a “focused and sequential strategy” that subordinates one country at a time, avoiding a regional war while tipping the balance of power in Beijing’s favor. Taiwan—just 80 miles from mainland China and, according to the Wall Street Journal, the source of “almost all of the world’s most sophisticated chips, and many of the simpler ones, too”—would be “the most attractive target.” Colby writes that “Xi Jinping himself has described this goal as ‘essential to realizing national rejuvenation.’”

Since Taiwan seems determined to preserve its freedom, China would have to seize control of key territory on the island. A successful fait accompli—which convinces the United States and its regional allies and partners as well as the Taiwanese that China’s gains are irreversible—would vitiate America’s credibility in Asia, Colby asserts. While the United States has assumed a variety of commitments to Taipei, Washington has refrained from entering into a formal agreement to preserve Taiwan’s independence and has maintained instead “strategic ambiguity” about how far the United States would go in the event of Chinese aggression. Failure by Washington to come to Taiwan’s aid to thwart a Chinese takeover of the island nation would show America’s allies and partners in the region that the United States is a paper tiger and would compel them to accommodate Chinese power.

The bulk of Colby’s deft analysis examines the steps that the United States must undertake to form an “anti-hegemonic coalition” to mount a successful denial defense in the Indo-Pacific, the intricacies of executing it, and the costs and risks that the United States would incur. While preventing the CCP from reunifying Taiwan with the mainland wouldn’t dispose of the China challenge, it would inflict a dramatic setback on the CCP and likely trigger a crisis of legitimacy for the party.

Although Colby warns against it, readers may come away from his book with the illusion that the China challenge consists in preserving Taiwan’s independence. That is crucial. But as “The Elements of the China Challenge”—an unclassified paper published in November 2020 by the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff (which I directed at the time)—argues, the China challenge goes well beyond the CCP’s determination to impose its will on the Indo-Pacific.

The CCP seeks not merely regional but also global preeminence. Its preferred means are not military but rather a variety of schemes of economic co-optation and coercion that emanate outward from the Indo-Pacific and reach all regions of the world. These include massive intellectual property theft, the commandeering of supply chains and critical materials, the quest for dominance in key 21st-century industries, Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure projects that induce in partner nations financial dependence and produce political subordination, and Chinese-built 5G networks that provide Beijing a steady pipeline of sensitive information and massive amounts of data for developing artificial intelligence algorithms. Study of the CCP’s ideas, rooted in Marxism-Leninism and traditional Chinese nationalism, shows that the party’s ambitions for national rejuvenation culminate in nothing less than placing Beijing at the center of a world order revised to favor authoritarian government.

American voters and political officials still have a considerable way to go in acquiring that knowledge of the CCP and its authoritarian ambitions—and of America and the strengths and limitations of its experiment in democratic self-government—that will enable our nation to secure freedom.

– – –

Peter Berkowitz is the Tad and Dianne Taube senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. From 2019 to 2021, he served as Director of Policy Planning at the U.S. State Department. His writings are posted at PeterBerkowitz.com and he can be followed on Twitter @BerkowitzPeter.

Photo “Xi Jinping” by Пресс-служба Президента Российской Федерации. CC BY 4.0.