by Carl Cannon

You wouldn’t think any possible controversy could append itself to that day, except that we are living in preternaturally contentious times. Two days ago, Rep. Cori Bush, a freshman Democrat from St. Louis, was testifying about racial disparities in health care, focusing specifically on childbirth. While describing her own medical experiences, Bush used the unwieldy phrase “birthing people” instead of “mothers.” Apparently, this was an awkward attempt to use inclusive language.

Predictably, this rhetorical gambit earned her a fair amount of ridicule on social media. I’m sure Rep. Bush has many virtues, but neither self-awareness nor self-deprecating humor are at the top of that list. Just as predictably, Bush lashed out at those who mocked her wording for their “racism and transphobia.” She also accused her critics of trivializing an important subject, which was a more substantive rejoinder. Bush was discussing racial disparities in America’s medical system, which is no laughing matter, and invoking her own harrowing experiences in hospital delivery rooms to do it.

Yet breezily trying to replace the word “mothers” as a sign of wokeness a few days before Mother’s Day wasn’t likely to go down well. It was Cori Bush’s own peculiar choice of words that distracted listeners from her story.

Born in Alabama, Zora Neale Hurston was 3 years old when her family moved to the Florida town of Eatonville. Although Eatonville was one of the first self-governing all-black municipalities in the United States — and her father was a prominent preacher and later the town’s mayor — his instinct was to shield his children from the dangers of Jim Crow. This overprotectiveness was one of the reasons the relationship between John Hurston and his fifth child was difficult. The parent who encouraged Zora’s artistic and restive nature was her mother, Lucy, who died when Zora was still a girl. But not before she helped stoke the fire inside.

Later, Hurston paid tribute to her mother with this passage in a 1942 autobiographical work: “Mama exhorted her children at every opportunity to ‘jump at de sun.’ We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

Maya Angelou, who wrote the preface to a later edition of that book, “Dust Tracks on a Road,” wrote about her own mother in several autobiographical works. In the most recent, “Mom & Me & Mom,” published in 2013, she relates a poignant exchange with her mother, Vivian Baxter, during the filming of Angelou’s screenplay, “Georgia, Georgia,” in Stockholm.

When things became difficult with the shooting of the movie, Angelou called her mother. Readers of Angelou’s previous books know that their relationship was just as fraught as Zora Neale Hurston’s was with her father. Nonetheless, Angelou wrote that when things became difficult, she phoned Vivian Baxter, then living in San Francisco.

“Mom, I need mothering,” she said. “If you have ever done any, I need it now.”

“Baby,” Baxter replied, “if any plane is leaving San Francisco today for Sweden, I am on it.”

She was as good as her word, and when she arrived in Stockholm, Baxter listened to her daughter’s account, and advised her that the men giving her trouble on the set would come around.

“In the meantime, Mother is here,” she added. “I will look after you and I will look after anybody you say needs to be looked after, any way you say. I am here. I brought my whole self to you. I am your mother.”

– – –

Carl M. Cannon is the Washington bureau chief for RealClearPolitics. Reach him on Twitter @CarlCannon.

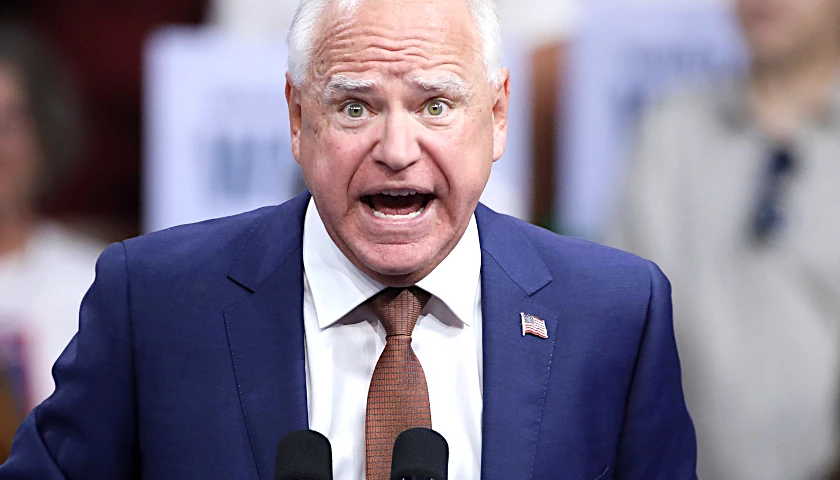

Photo “Maya Angelou” by Kingkongphoto & www.celebrity-photos.com CC 2.0.