The First Gulf War, or Desert Shield and Desert Storm, which was a strategic failure, but an operational success came to an end Feb. 28, 1991 with President George H.W. Bush calling a halt to combat operations after the 100 hours of combined land and air offensive.

It was the culmination of months Desert Shield’s diplomacy and military build-up beginning Aug. 7, 1990, shortly after Iraq invaded and conquered its neighbor Kuwait. Desert Storm began Jan. 16, 1991 with a ferocious air campaign that prepared the battlefield for the last 100 hours.

It is important to record operations success in the ledger of a war whose memory has become awkward and difficult.

Few wars have been so celebrated as victories, and then severely denigrated as the action against Saddam Hussein and forces occupying Kuwait.

Seen through the lens of the President George W. Bush’s own war in Iraq, the second conflict dwarfs the first in blood and treasure expended – and begs us to ask how much of our foreign policy and war making was some playing out of unresolved father-son issues.

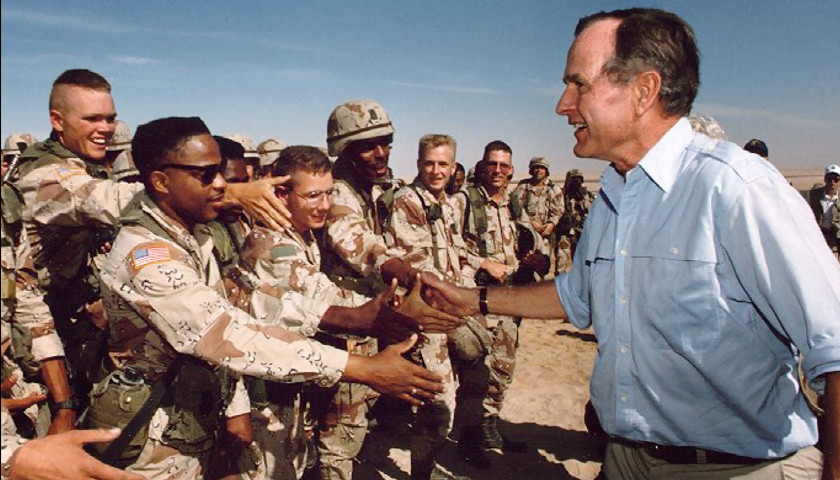

A month before Bush ordered the cease fire on the retreating Iraqi Army, he spoke Jan. 23, 1991 to the Reserve Officers Association’s annual dinner and accepted the “Minuteman of the Year” award.

In his remarks, Bush said: “Turning a blind eye to Saddam’s aggression would not have avoided war – it would have only delayed the world’s reckoning – postponing what ultimately would have been a far more dangerous conflict.”

Setting aside the discussion about whether the elder Bush should have marched straight on to Baghdad or at least should have continued to decimate the retreating Iraqis jammed all roads north, the First Gulf War validated the development of America’s post-Vietnam military.

It was this validation the fueled the celebrations with that sense of relief that the United States, post-Vietnam, was actually capable of successfully waging war on the other side of the earth.

First Gulf War Proved the All-Volunteer military a success

Part of that validation was the success of the All-Volunteer military that began Jan. 27, 1973, when President Richard M. Nixon ended the draft.

During the build-up in Vietnam, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara made the decision to rely more on conscripts, rather than to rely on calling up reserve and National Guard units. This was a cheaper way to run a war, yet it created incredible turmoil in the families and communities affected.

Nixon promised to end the draft in his 1968 campaign, partly on the advice of Chicago University economist Milton Friedman, who argued the draft was the unfair government abuse. For Nixon’s plan to work, the reserve components of the different services and the National Guard had to become what draft had been.

More than 150,000 reserve and National Guard personnel were mobilized for Desert Shield and Desert Storm, and roughly 73,000 deployed to the Middle East. There were some problems and lessons to be learned, but in virtually every instance, the reserve units and personnel blended in with their active-duty counterparts.

This success of the Total Force concept, put to rest any talk of bringing back the draft.

Five major weapons systems proved their worth

After the Vietnam War, the U.S. military underwent a tremendous transformation.

The 500,000 soldiers, airmen and Marines the Pentagon was fielding in Southeast Asia were a counterinsurgency and air mobility force.

Ten years later, the word counterinsurgency was no longer used in the manuals.

The centerpiece of the air mobility in Vietnam, 1st Air Cavalry Division, which lost more than 5,000 men in Vietnam. When Desert Shield began, it was now the 1st Cavalry Division, and it was in essence a tank division went stepped off to take on the Iraqi Army in Kuwait.

The transformation of 1st Cavalry replicated across the Army and key to this transformation was the Pentagon’s heavy investment into five major weapons systems: the M-1 Abrams tank, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the Apache attack helicopter, the Black Hawk helicopter, and the Patriot Missile System.

The M-1 Abrams tank

The M-1 Abrams tank was appropriately named for Army Gen. Creighton Williams Abrams Jr., who led U.S. forces in Vietnam from 1968 to 1972, and then Big Army from 1972 until his death in 1974. Abrams had been a tank battalion commander in World War II, but more importantly, he was a man of his age, who stabilized the Army coming out of the Vietnam experience and kicked off its transition from a counterinsurgency force back to a big power conventional force.

The Abrams tank came into service in 1980, and by 1990, it was already the main battle tank for both the Army and the Marines.

In Desert Storm, the Abrams outmatched the Iraq’s Russian-built T-55, T-62 and T-72 tanks by every possible measure. Most importantly, the Abrams had a range of 8,200 feet compared to the best range of the Iraqi tanks at 6,600 feet. With that more than a quarter-mile range advantage, no Abrams received a direct hit from an opposing Iraqi tank and there were no enemy-inflicted deaths from Iraqi tanks crews.

The Bradley Fighting Machine

The Bradley Fighting Machine was also named for a more conventional general, Gen. Omar N. Bradley, the last living of the nine five-star generals and admirals from World War II. Bradley said that Vietnam was: “The wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time and with the wrong enemy.” This aligned him perfectly with the Army’s emotional retreat from Vietnam.

The Bradley, a combined personnel carrier and tank killer, came online in 1981 – and like the Abrams – was heavily criticized a Pentagon boondoggle. Three years before the Gulf War, HBO aired the movie “Pentagon Wars,” starring Kelsey Grammer about the corrupt practices the military employed to develop the Bradley.

However, in actual desert combat, the Bradley excelled.

Previous armored personnel carriers could not keep up this the Abrams, but because the Bradley could, the two vehicles could work as a combined arms tandem with the Bradley’s six dismounted infantrymen, its 25mm automatic gun for clearing bunkers and its highly accurate TOW anti-tank missile.

In the Gulf War, only three Bradley vehicles were taken out by the Iraqis out of the 2,200 put in the field. Several sources credit the Bradley with even more Iraqi tank kills than the Abrams.

The Apache

During the Vietnam War, the heavy focus on air assault and air mobility proved the worth of helicopters. As the Army became a tank-on-tank force, it needed a tank killer aircraft that could also function in a combined arms construct with land forces.

Because of the 1948 Key West Agreement between the branches of the armed forces, the Army could not field fixed-winged aircraft, so it had to develop a helicopter for the mission.

In 1986, the Apache AH-64 entered the inventory armed with Hydra 70 rockets, Hellfire missiles and a 30mm chain gun.

In 100 hours of Desert Storms land offensive, there were 277 Apache in the offensive and they killed 278 tanks. Only one Apache was shot down, and it was felled by a rocket-propelled grenade. In that crash, the crewmembers survived.

The Black Hawk

The Apache is a fierce and deadly weapons system that is often pitted against fighter jets in fantasy matches, but the American military’s work horse helicopter is the Black Hawk UH-60.

In the Gulf War, 300 Black Hawks were deployed, mostly as air assault troop transports, a throwback mission to the air calvary of the Vietnam War. The Black Hawks were also used as medical evacuation, or medevac, aircraft and for light cargo. As a airborne truck, the Black Hawk does not have organic weapon systems, but relies on door gunners manning automatic chain guns.

In the last days of Desert Storm, two Black Hawks were shot down while they were searching for lost air crewmembers.

The Black Hawk began its service in 1979, and in the Gulf War it came into its own as the reliable utility helicopter it was supposed to be. Two years after the Gulf War, the Black Hawk would be immortalized in the Battle of Mogadishu and the book and movie about the action there, “Black Hawk Down.”

The Patriot Missile

The MIM-104 Patriot Missile was the closest thing to a magic trick the U.S. military ever produced.

The Patriot came into service in 1984 as a surface-to-air system designed to take down aircraft, but it was literally reprogrammed to track and to take out the dreaded Iraqi Scud missiles.

Videos of Patriots taking down Scuds enthralled Americans watching this very-televised war back home. The Army reported that the Patriot batteries in Saudi Arabia had a 70 percent success rate against the Scuds and a 40 percent success rate for batteries positioned in Israel.

When a Patriot took down its first Scud Jan. 18, 1991 over Saudi Arabia, it was the first time an air defense system destroyed a hostile tactical ballistic missile.

Patriot missiles were so popular a weapon system that the Left became obsessed with denigrating the missiles and even going so far as to claim that the videos of Patriots taking down Scuds were some kind of optical illusion – and that the Patriot did not work at all, nor did it hit any Scuds.

None of the attacks by the Left and their allies in the media held up to scrutiny, and there is no greater proof of the system’s effectiveness than the continued use of the Patriot by the U.S. military and other militaries around the world.

Prince Bandar bin Sultan bin Abdulaziz Al–Saud, then the Saudi ambassador to the United States, became one of the most fervent defenders of the Patriot missile and its record during the Gulf War.

“It’s very nice and very easy to be a critic 8,000 miles away in an air conditioned office, but ask me. I was there and the most beautiful sight in the world that I have ever seen in my life was that Patriot streaking across the capital of Saudi Arabia hitting those Scuds,” the ambassador said. “Don’t listen to people who think they are playing video games. That was no game.”

The legacy of the First Gulf War

Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm seemed like massive and important events and the what was described as a great victory now rings hollow.

Despite the 500,000 U.S. troops, roughly the same number that were in Vietnam at its peak, and the more than 18,000 air deployment missions, 116,000 combat air sorties and 88,500 tons of bombs – maybe Bradley would have said of the First Gulf War: “The wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time and with the wrong enemy” just as he did Vietnam.

Regardless geopolitical consequences of the Liberation of Kuwait, it was absolutely and operational success, as it demonstrated the ability of the United States to lift men, equipment and materiel eight time zones from Washington.

The Gulf War also validated the Nixon’s promise that an All-Volunteer military supplemented by reserve and National Guard units and personnel would perform better than the military had using conscripts – and with less societal tumult.

Finally, as the U.S. military transitioned doctrinally and emotionally from its Vietnam posture, the Pentagon bet billions of dollars on five major weapon systems that many on the Left and in the media criticized as wastes of money. Yet, each of those systems, the M-1 Abrams tank, the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the Apache attack helicopter, the Black Hawk helicopter and the Patriot Missile System remain at the heart of our force structure 30 years after they proved their worth in the Gulf War.

– – –

Neil W. McCabe is a Washington-based national political reporter for The Tennessee Star and The Star News Network. In addition to the Star Network, he has covered the White House, Capitol Hill and national politics for One America News, Breitbart, Human Events and Townhall. Before coming to Washington, he was a staff reporter for Boston’s Catholic paper, The Pilot, and the editor of two Boston-area community papers, The Somerville News and The Alewife. McCabe is a public affairs NCO in the Army Reserve and he deployed for 15 months to Iraq as a combat historian.