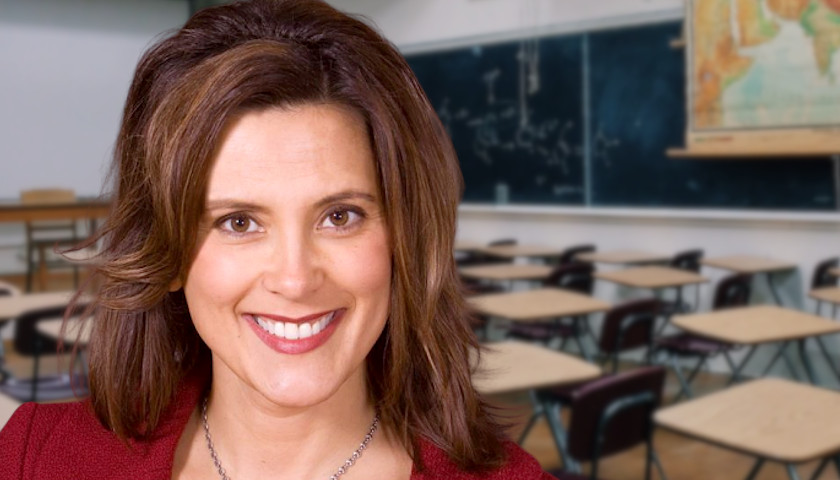

When Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer (D) line-item vetoed a $155 million program for K-5 reading scholarships in the $17 billion school budget she signed earlier this month, teachers’ unions and other school choice opponents likened the scholarships to vouchers.

Many proponents of the scholarship expenditure are responding that while they would welcome broader choice-oriented education reform, a plain reading of the program does not jibe with unions’ and school administrators’ stated concerns about the impact on public education.

A proposed allocation of federal COVID-19 relief funds, the literacy grants would have been disbursed by Grand Valley State University in the amount of $1,000 each to elementary-school-age students who have not reached reading proficiency benchmarks. Parents would have been able to use the money to hire tutors, enroll their children in summer and afterschool courses, or purchase instruction materials. Republicans, who hold a majority in the state House, attempted to override Whitmer’s veto but lacked the two-thirds vote needed to do so.

Bob McCann, executive director of the school-administrator group K-12 Alliance of Michigan, has called the scholarship allotment “a large pot of money [that] smelled a bit of vouchers.” When Whitmer signed the education budget and struck the literacy grants, David Hecker, president of AFT (American Federation of Teachers) Michigan, called her “a strong advocate for Michigan’s public schools …” The Michigan Education Association also praised the governor as she signed the school funding without the scholarship item.

Ben DeGrow, director of education policy at the free-market Mackinac Center for Public Policy, has, however, advised critics of the program to take a closer look at how it would have been funded and how it would have worked.

“The reading scholarships that have been proposed here in Michigan definitely would be good from the standpoint of giving many families of struggling readers an opportunity to supplement the reading instruction they’re getting, to get help from tutors of their choice, to get help from instructional materials and things they might not otherwise be able to afford,” DeGrow told The Michigan Star.

He pointed out that Michigan students’ reading scores were stagnating even before COVID-19 countermeasures kept kids out of schools during much of the pandemic. Results of the Michigan Student Test of Educational Progress in 2019 showed merely 44.3 percent of children in grades three through seven reading at standard levels. DeGrow characterized the literacy scholarships as a well-crafted means to address the problem drawing from the experience of states like Florida that have pioneered such programs.

What’s more, he said, because the grants would have come from one-time federal COVID-19 relief funds, they would not be depriving other programs of any money. While liberals like state Representative Regina Weiss (D-Oak Park) have said the money would be better spent directly on literacy instruction within public schools, DeGrow pointed out that “there’s nothing in the budget that passed that took anything away from literacy coaches …”

Other education reform advocates have shared DeGrow’s disappointment in Whitmer’s veto. Former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, a Michigander, wrote an op-ed in the Detroit News calling the decision “indefensible.”

As this article goes to press, neither the governor’s office, the Michigan Education Association, or AFT Michigan returned requests for comment.

– – –

Bradley Vasoli is a reporter at The Michigan Star and The Star News Network. Follow Brad on Twitter at @BVasoli. Email tips to [email protected].