by Kevin Killough

In the wake of widespread fears of climate change, an entire new field of psychotherapy has sprung up to treat what is being called “climate anxiety.”

Climate-aware therapists are specialists who treat people whose anxiety about climate change interferes with their enjoyment of life. These specialists are now available in just about every major city across the United States.

The degree to which climate change will pose risks to people in the future is far from certain, and the human race is today safer from climate than it was 100 years ago. The number of deaths from climate-related natural disasters has fallen 99% since 1920.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations consortium of the world’s leading climate researchers, has five emissions scenarios — with and without policies to mitigate them — called Shared Socio‐Economic Pathways (SSPs). Under every scenario, the human race is, to one degree or another, better off economically in 100 years than it is today.

Despite these facts, many people, especially young people, are experiencing serious anxiety over climate change. A 2021 Lancet surveyof 10,000 people aged 16-25 years, found that 59% were very or extremely worried and 84% were at least moderately worried. Nonetheless, a few months later the same esteemed British medical journal published an article titled “Climate anxiety does not need a diagnosis of a mental health disorder.”

Certainly abusive

Linnea Lueken, research fellow with the Heartland Institute, told Just the News that it’s the media that are driving these overwhelming fears of climate change and ignoring evidence that would calm anxieties. She said climate reporters’ impact on children, as shown in the Lancet survey, raises a moral question.

“It’s certainly abusive to be telling kids they don’t have a future,” Lueken said.

Dr. Matt Wielicki, former assistant professor in the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Alabama and publisher of “Irrational Fear,” told Just the News that as a professor he became concerned about the narrative on climate change when he saw the distress many of his students were experiencing over what they believed about global warming.

“I think this is the first generation where they’ve their whole lives that the planet is on its way to ending at some point in their lifetime, civilization is going to collapse and the food supply will be destroyed,” Wielicki said.

From what they’re being told on a daily basis, he said, he doesn’t blame them for being anxious about it.

“We’ve really manipulated their sense of the future, and that’s unfortunate, because it really takes away their hope and ambition,” Wielicki said.

Two prongs

Lueken said there’s two prongs to the problem with how the media cover climate change — one that is a natural extension of the evolution of technology, and the other is an intentional effort on the part of activists.

With the expanded access to information that people have today thanks to the internet, Lueken explained, natural disasters and chaotic weather events are pumped into people’s computers and phones on an hourly basis from across the globe.

“Even just 50 years ago, you wouldn’t know what the weather was today in Thailand. You wouldn’t know if there was a typhoon that hit India,” she said.

Thrusting disasters in front of people on an hourly basis, Lueken said, creates the perception that weather is out of control and becoming more extreme by the day. Add to that the fact that climate science is complex, she explained, and understanding all the studies and data to get an expert-level understanding of what’s happening with climate is far outside the scope of what most people have time for. So, much of what they know is what they see on the internet.

The other prong is the intentional effort on the part of activists groups to spread climate fears throughout the media. Groups like Covering Climate Now and the Society for Environmental Journalists — both of which are funded by anti-fossil fuel groups — encourage reporters to insert climate change into every story in the most sensational ways possible. They also discourage reporters from presenting countering perspectives.

These groups reach hundreds of climate and energy reporters working at hundreds of media outlets. Covering Climate Now boasts of reaching an audience of over 2 billion people across the globe.

“Covering Climate Now is a toxic wasteland of an organization. They’re the reason why you have all these stories that seem to have nothing at all to do with climate change, that they’ll still tie to climate change,” Lueken said.

A recent example of this was sinking of British tech tycoon Mike Lynch’s yacht off the coast of Sicily. Multiple outlets — including The Guardian, which was a co-founder of Covering Climate Now — reported that the storm that sank the boat was “climate fueled.” Ships have been sinking in storms for far longer than carbon dioxide emissions have had an effect on climate, but in the media environment today, even a tragic event involving a single ship is blamed on climate change.

“It’s all a big part of the structured narrative of climate catastrophe,” Lueken said.

Another dimension of the problem is social media, she said. Young people enter echo chambers where these distorted pictures of climate change are shared and re-shared to create an echo chamber that reinforces the narrative.

Paralyzing fear

Besides the impacts on mental health, this perpetuation of incessant fear about climate change may, ironically, undermine action to address the problem. While activist groups pushing media narratives hope that a barrage of scary stories will encourage action, studies are finding that this approach actually has the opposite effect. These messages eventually desensitize audiences, undermine trust, and paralyze them with hopelessness.

“It’s the worst way to make someone think about long-term protection of the environment. It’s the worst way to motivate somebody to be a good steward of the planet,” Wielicki said.

Wielicki said that if people are going to address climate change in any kind of constructive way, the message in the media needs to shift to something more constructive.

“I wish everybody would start ratcheting down the rhetoric. And I think you’d see a lot more progress and a lot more hope,” he said.

“Climate anxiety” is not officially recognised as a condition or a mental health disorder in the diagnostic manuals such as the DSM, relied upon by psychologists, psychiatrists and other health professionals. In fact, many researchers and health professionals are debating whether “climate anxiety” is genuinely a recognizable disorder.

The Climate Psychiatry Alliance formed to “educate the profession and the public about the urgent risks of the climate crisis, including its profound impacts on mental health and well-being.” In a section on its website on resources to help people cope with climate anxiety, the alliance encourages those suffering from such anxiety to “resist the tendency to catastrophize.” It suggests that people avoid seeing only the negative, counter doom scenarios, and be aware of counter-balancing stories.

That may be good advice for climate reporters, too.

– – –

Kevin Killough is a reporter for Just the News.

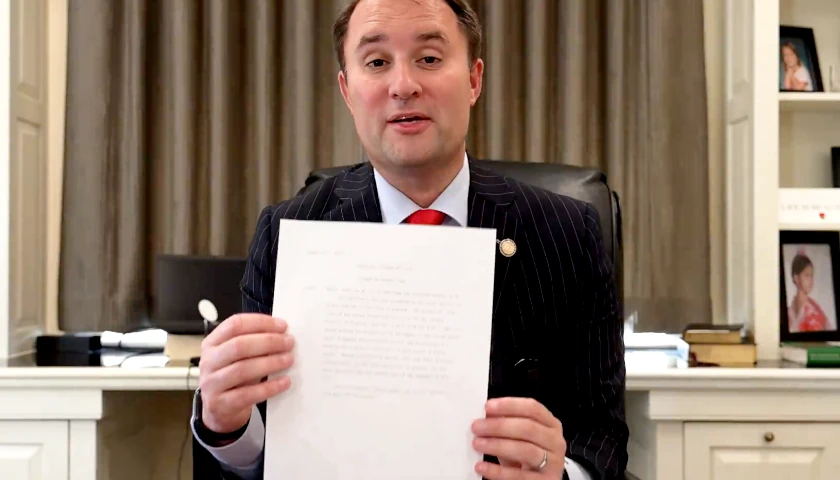

Photo “Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change” by Rick Bajornas.