The Biden Department of Justice (DOJ) issued a 126-page report on Thursday claiming that it found probable cause after a three-year investigation that the Phoenix Police Department (PPD) violated the First, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments when dealing with the public.

The investigation began in August 2021, alleging five problem areas. The DOJ accused PPD of using excessive force, discriminating against nonwhites, treating homeless people unlawfully, violating the First Amendment, and discriminating against the mentally ill.

But a longtime PPD officer told The Arizona Sun Times that “the report was full of inconsistencies and fabrications.” He said any of the incidents they list can easily be debunked. He said it was outrageous that Phoenix Chief of Police Michael Sullivan doesn’t defend PPD and call the DOJ out for it’s “bull***** investigation,” instead he provides “spineless fluff.”

He noted that the DOJ’s report last year on the police department in Louisville, Kentucky, was very similarly written. He told The Sun Times he suspects the DOJ has a template that they use to target police departments “city by city.”

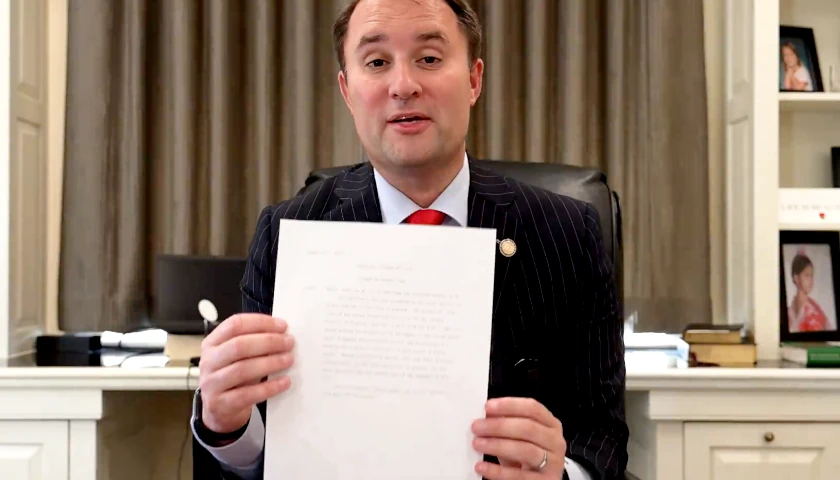

The Phoenix City Council will decide on June 25 what to do next. The policeman said they should take it to court and fight. Unlike many other cities, Phoenix has a city council, not just a mayor and city manager, which makes most decisions. Four of the nine members – eight council members plus the mayor – said they will not sign a consent decree, which would place PPD under the DOJ’s supervision for years.

Cornell Law’s Legal Information Institute website defines a “consent decree” as a binding agreement (decree) made by a judge with the permission (consent) of the parties – in this case, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Phoenix Police Department.

The site adds that consent decrees are “often used in government regulation” in lieu of further legal action against the other party.

The law enforcement officer said it was unprecedented for the DOJ to release its report without requiring an agreement to a consent decree first, adding that there are rumors within the department that Sullivan, the city manager, and the DOJ had secret meetings agreeing to a backroom deal that will result in one.

The DOJ demanded so much information, the officer said, that it required a team inside the police department to facilitate it all. A sergeant and lieutenant were initially placed on the team, but when they refused to sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement that would bar them from discussing their work, they were asked to leave.

Another Phoenix PD officer told The Sun Times that there were all kinds of problems with the report. He said the consultants hired by the DOJ to visit PPD were fresh out of law school and knew nothing about law enforcement. He said they pulled a few files and didn’t interview relevant people. There was a lot they didn’t do, he said. Additionally, the cases cited in the report are old, and key details were omitted from the report, including that those cases were resolved.

PPD has been working to address the complaints since the DOJ first began its investigation, releasing a 53-page Road to Reform plan in January. PPD adopted a new limit of force policy focusing on de-escalation last year.

The report said, “PhxPD officers shot and killed people at one of the highest rates in the country,” but didn’t mention until much later that Phoenix is the fifth most-populous city in the country. Nor did it mention that the city faces higher crime due to the porous border with Mexico, which is wide open under Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs. The report never mentioned that PPD is confronting violent cartel members and dangerous criminals coming across the border from all over the world and instead blamed them for having to deal with the increased violence.

The DOJ said sending social workers instead to respond to many 911 calls, especially ones involving violence caused by hard drugs, was better than sending officers.

“Too frequently, they dispatch police alone when it would be appropriate to send behavioral health responders,” the report said.

The DOJ used confusing language regarding disabilities, implying that regular people with traditional disabilities were encountering hostile situations with the police, not people with drug problems who were engaging in violence.

“Officers act on the assumption that people with disabilities are dangerous and rarely modify their approach. Officers resort to using force rather than de-escalation tactics that would likely help a person with behavioral health disabilities follow directions,” the report said on page 6.

The report attempted to blame the alleged problems on segregation and racial strife, claiming that non-white communities have been relegated to the south side of Phoenix due to discriminatory real estate practices. However, Phoenix is 43 percent Hispanic, 7 percent Black, 4 percent Asian, and 2 percent Native American. It would be impossible to funnel 56 percent of these nonwhites into the south side.

Even though the PPD’s chief of police during the last few years examined by the report was a black woman, the report claimed that the PPD “uses race or national origin as a factor when enforcing traffic laws,” “enforces alcohol use offenses and low-level drug offenses more severely” against minorities, and “enforces quality-of-life laws, like loitering and trespassing, more severely.” (page 55)

It failed to discuss factors like how someone lurking around a particular location might fit the suspect’s description, causing officers to be more suspicious of that person and likely to stop them. The DOJ claimed that minorities were more likely to be cited for infractions like improper license plate lights and improper window tinting, but it failed to provide additional details, such as what other infractions, such as reckless driving or drunk driving, accompanied them and likely spurred those as secondary citations.

A study from the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office released in 2008 found that illegal immigrants commit twice as many crimes as their percentage of the population: 21.8 percent of crimes versus 9 percent of the population.

The DOJ claimed racism must have caused the discrepancies since traffic red-light cameras and speed cameras recorded a breakdown of offenses between the races based on their percentages in the population. However, the cameras didn’t track other offenses, such as a more serious offense that might have triggered an officer to pull over a driver.

The report admitted that PPD said the department was “unaware of any credible evidence of discriminatory policing.” (page 5 and 66)

It denounced PPD officers for making “racist statements” on social media over “posts calling Kwanzaa a ‘fake holiday’ and celebrating armed self-defense against ‘thugs’ in ‘saggy pants.” (page 67)

The DOJ said that PPD’s Compliance and Oversight Bureau and Center for Continuous Improvement weren’t adequately looking for racism, since they only provided “quality assurance,” not “high level review.” (page 68)

The DOJ took the word of people who were pulled over for traffic stops that it was due to racism, quoting their remarks. The DOJ admitted that “investigators classified the complaints as officer ‘rudeness.’” (page 69)

The report said that PPD didn’t find more racism.

“[A]ll 90 administrative inquiries into allegations of ‘bias or racial profiling’ during the same time period, investigators found that the allegations were ‘unfounded’ or that the officers were ‘exonerated,’” page 70 of the report said.

The DOJ faulted management for dismissing complaints where “the officer ‘never said, ‘I am stopping you because you are Black’” and “the PhxPD employee did not comment on the man’s race or admit to racial profiling.” (page 71)

The report is peppered with emotional language. “Being stopped by police can also cause psychological harm, especially when it happens repeatedly,” the DOJ said on page 71. “And when an encounter results in a use of force, the physical and emotional scars can be permanent.”

One of the examples the report cited as unreasonable force involved officers shooting a robbery suspect who moved towards them after they warned him not to or they would shoot him. They shot him in the abdomen, so he apparently survived. (page 16)

Another incident the report criticized involved a suicidal woman who told the officers, “You better call for backup,” then pulled out a gun so the officers shot her. (page 19)

A section of the report criticized officers for allegedly waiting too long to see if the suspects they had shot were still alive and needed medical treatment. It failed to mention any details about the officers’ concerns for their own safety. (page 19)

The report left out key details, such as whether suspects were on methamphetamines or other hard drugs, even though throughout the document suspects are described as either in a “behavioral health crisis” or “behavioral health disabilities” more than 50 times.

The report said PPD’s use of less-lethal force, which includes firing Tasers and releasing police dogs. None of the incidents covered stated that any suspects required serious hospitalization. This was the same as the DOJ’s criticism of how officers used leg restraints, Tasers, and police dogs.

The report repeatedly stated, “Phoenix has trained its officers that all force — even deadly force — is de-escalation.” However, it cited little evidence. Some of the statements appeared to be lacking context. “Indeed, in some trainings we observed, trainers encouraged officers to use force without warning or just seconds after arriving at a scene, regardless of whether the person presented an apparent risk to officers or others,” the report said. (page 5)

Also, the report faulted a trainer for stating that an officer who told a suspect to get out of the car with his hands up, who was “moving around and yelling” while doing so, should be shot.

The report said about small uses of force not requiring supervisory reviews, such as “pushing someone’s nose with an officer’s hand.” (page 39)

The DOJ claimed, “PhxPD’s failure to meaningfully review force incidents validates and reinforces unconstitutional practices.“ (page 39)

The section in the report alleging violations of the First Amendment heavily relied on one instance involving a violent protest by Antifa. Former longtime Maricopa County Prosecutor April Sponsel attempted to prosecute Antifa members rioting after George Floyd’s death, but after ABC15, which has relentlessly attacked local law enforcement in articles in recent years, covered the story unfavorably towards PPD, MCAO changed its mind.

“On February 12, 2021, MCAO dismissed the gang charges against protesters following a week of intense scrutiny because of ABC15’s reporting,” the news site said.

However, the report didn’t include that, stating, “Following the protests of 2020, PhxPD and the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office falsely claimed that 15 people arrested at a protest were members of a criminal street gang and sought charges against them that carried multiyear prison sentences.” (page 9)

The report attempted to downplay Antifa’s actions, focusing instead on how the officers handled them. The report left out pertinent information, such as that PPD circulated a memo before the October 17, 2020, riot stating that the protesters intended to disrupt traffic, get arrested, and go to jail. The Arizona Bar’s disciplinary counsel in Sponsel’s disciplinary case acknowledged that the protesters marched in the middle of the streets, moved traffic barricades into the street, carried umbrellas to shield their behavior, deployed at least two smoke bombs, and flashed lights at the police. One carried firearms. Officers ordered them to disperse, and 18 of them were arrested when they refused.

Sponsel was fired after her superiors, who had unanimously agreed to bring gang charges against Antifa, changed their minds. The State Bar of Arizona suspended her license to practice law for two years.

Much of the report appeared to copy language verbatim from ABC15 and possibly the ACLU of Arizona. For example, it stated on page 77, “The judge handling the case called the claim that the protestors were members of a criminal street gang ‘false, misleading, and inflammatory.’” This was reported by both entities.

The report cited how PPD arrested protesters who were ultimately never prosecuted for crimes. However, it contained no discussion of the pressure that was put on MCAO to dismiss the charges.

The rest of the coverage of PPD’s handling of violent rioting also left out select details regarding the behavior of those accosted and arrested.

A photo of rioters on page 79 showed them blocking an entire lane (pictured here), yet the caption stated, “PhxPD arrested protestors for obstruction of a thoroughfare when they did not interfere with traffic.”

That section ended with discussion about the First Amendment and democracy. “Political speech is ‘central to the meaning and purpose of the First Amendment.’ Protecting this speech, which is ‘indispensable to [decision-making] in a democracy,’ secures ‘confidence and stability in civic discourse,’” the report said. (page 86)

Regarding the homeless, the report admitted that the number of homeless people has nearly tripled over the past decade, reaching almost 3,500 “unsheltered.” It also admitted, “PhxPD’s public policy is to ‘lead with services,’ and this stated policy has encouraged officers to make referrals, not arrests.”

The DOJ stated on page 5, “Like many other cities, Phoenix has a significant unhoused population.” Phoenix’s homeless encampment near downtown, known as “The Zone,” became such a nuisance, at times ballooning to over 1,500, that a judge ordered it disbanded in 2023.

“The practice of stopping, citing, and arresting unhoused people was so widespread that between 2016 and 2022, 37% of all PhxPD arrests were of people experiencing homelessness,” the DOJ said. However, the report failed to state that this was not a relatively high rate. In Portland, about half of all arrests are of homeless people.

The report claimed, “Many of these stops, citations, and arrests were unconstitutional.” It said officers routinely stop homeless people without reasonable suspicion, but they didn’t list what the officer put in his report about what the reasonable suspicion was. (page 5)

Instead, the report was full of statements like, “Although the officer had no basis to suspect criminal activity, he stopped the man to check for warrants anyway.” (page 45)

Similarly, the report concluded that officers detained homeless people “for no reason other than that they are sleeping in public. Without suspicion of a crime, these early morning detentions are unlawful.” (page 46)

Again, the report failed to state what the officers put in their police reports for reasonable suspicion. There is no mention of any crimes they may have been in the process of committing.

PPD was criticized for telling a group of homeless they were not allowed to camp but admitted that the U.S. Supreme Court has yet to decide whether “punishing a person for sleeping outdoors, when they have nowhere to go, is cruel and unusual under the Eighth Amendment.” (page 46)

One incident cited a prosecutor declining to press charges against a homeless man for trespassing because they were “a little iffy.” However, the description was sparse and didn’t explain why the officers fired a Taser at him and pushed him to the ground. Nor did it explain why the prosecutor was concerned — the concern could have had nothing to do with the validity of the charges but many other types of reasons, such as someone spilled coffee on the police report accidentally, so there was no proper evidence.

Much of the report treated statements by homeless people as facts. For example, it stated that PPD violates the Fourth Amendment by destroying property during clean-ups, with an extensive section reviewing those incidents. However, PPD has made thorough progress in logging and storing property seized this way, allowing suspects to pick it up later. The process involves driving to the storage location, waiting in line, showing identification, etc. The report didn’t look into whether this complex process, especially the requirement to show ID, was why the homeless did not get their property back.

The section on how PPD handles people with behavioral health issues assumed that it is better to send social workers instead of law enforcement but included no information about how violent people can be when high on methamphetamine, cocaine, fentanyl, and other hard drugs. They reported how officers took actions they disagreed with but didn’t reveal what prompted the officers to do so.

The report criticized 911 operators for labeling certain calls as “fights,” which were later changed by the responding officers to codes like mentally ill, drunk, disturbing, or trespassing. It claimed that “a non-police response would generally be considered appropriate.” (page 91)

A section that begins on page 101 of the report titled “PhxPD Fails to Modify Practices During Encounters with Children” dealt with PPD confronting teenagers who may have been violent gang members but were not identified as such. The report said that the officers were not gentler. A photo showed an officer pulling one up by the scruff of his shirt when he refused to stand up, implying that it was mistreatment.

The few genuinely disturbing actions by PPD are interspersed throughout the report with the cherry-picked accounts, making it difficult to distinguish them.

The report ridiculed a trainer’s use of humor during class as if it was part of the alleged wrongdoing.

The report admitted that the courts are forcing PPD to spend millions in taxpayers’ dollars to settle alleged wrongful treatment lawsuits. The lawsuits get extensive media attention all throughout the process. “Between 2016 and 2023, the City paid over $40 million to settle claims of police misconduct in no fewer than 75 claims or lawsuits. In 2023 alone, the City settled cases for more than $12 million; there are outstanding claims asking for millions more,” the report said. (page 105)

The DOJ concluded its report with recommendations, mostly to “improve policies and review procedures” in numerous areas. One section was “Identifying and Reducing Racial Disparities.”

– – –

Rachel Alexander is a reporter at The Arizona Sun Times and The Star News Network. Follow Rachel on Twitter / X. Email tips to [email protected].

Photo “Phoenix Police Department Officer” by Phoenix Police Department.