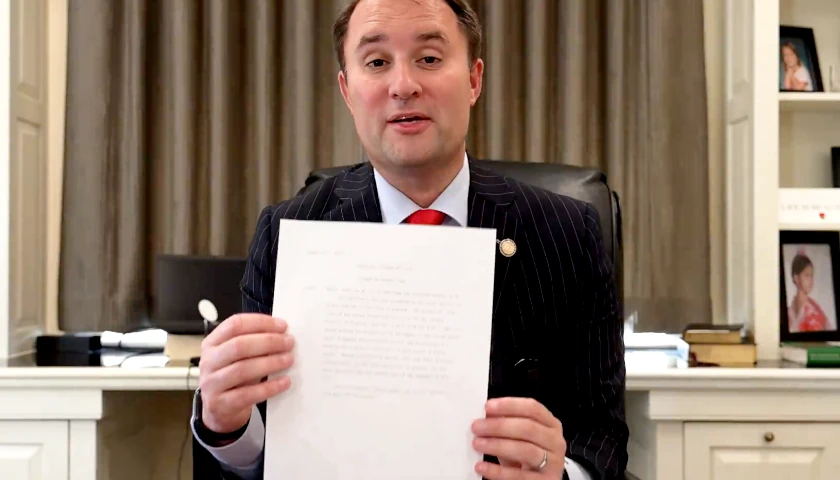

by Kurt Mahlburg

This weekend will mark my first Father’s Day as a dad—an occasion I will relish.

Our 10-month-old daughter, Elsa, has a personality that is larger than life, and the bond I have with her, even at such a young age, is precious beyond words.

One thing I have pondered often these past ten months is the distinct and irreplaceable benefits that children derive from both their mother and father.

My observation that fathers are irreplaceable is not intended to be self-congratulatory. Rather, it is a truth woven into the very fabric of the universe that long predates my short life on this planet.

A loving and involved father, even one with a long list of flaws, will by his very nature foster emotional resilience in his children, encourage risk-taking and independence, and enhance their cognitive, academic, and social intelligence.

This fact holds true whether or not he is familiar with the vast research on the subject.

While it will be many years before these benefits are on full display in Elsa’s life, I have already noticed an obvious contrast in how she relates to me and my wife, Angie. Our baby is also ignorant of the research, but she knows intuitively that what I have to offer her is qualitatively different from what her mother can provide.

Elsa knows to call out “Mama” when she needs comfort, especially as bedtime draws near or if she wakes during the night. Nothing relaxes her like Angie’s embrace. I have tried to replicate the same positions, postures, and pats for Elsa but to no avail. It is not a question of technical skill. Angie is her mother, and I will never be.

Likewise, I am Elsa’s father, and Angie will never be.

If our baby wants to be thrown up in the air, pushed higher on the swing at the park, or left to navigate some of her daily challenges with verbal affirmation instead of direct support, she knows where to look. I don’t set out to be specifically “masculine” in these ways—I have simply noticed that this is how I am wired to operate.

Writing for Public Discourse, leading family researcher Jenet Erickson explains that “a mother’s capacities are uniquely oriented toward identity formation and emotional security.” She continues:

From infancy on, children are more likely to seek out their mothers for comfort in times of stress. And mothers are much more likely to identify, ask about, listen to, and discuss emotions with children. A mother’s unique orientation toward identifying, expressing, regulating, understanding, and processing emotions is not only important for self-awareness and emotional well-being; it also lays a foundation for moral awareness, including a sense of moral conscience with the capacity to distinguish between right and wrong.

What fathers provide is just as important, but altogether different:

First, compared to mothers, fathers’ interactions are characterized by arousal, excitement, and unpredictability in a way that stimulates openness to the world, with an eagerness to explore and discover. Second, fathers have a unique ability to encourage risk-taking while ensuring safety and security, thus inviting children to pursue opportunities that translate into educational and occupational success. Third, involved fathers consistently focus on helping children learn to do things independently and to find solutions to their own problems, building both capacity and confidence. Finally, fathers tend to be more ‘cognitively demanding’ of their children, pushing them to deepen and demonstrate their understanding.

Far from being the opinion of just one women, decades of social research affirm the importance of a married mother and father in the life of a child and the unique roles each parent plays.

The longer Angie and I parent together, the more these differences become apparent.

I have a high tolerance for Elsa’s tears. For Angie, something primal in her takes ahold when she hears our baby cry.

I was the first to introduce Elsa to the adrenaline of twirling and hanging upside down. Angie was the first to bring her into our bed for morning snuggles.

I can’t wait to take Elsa camping, bike riding, and kayaking. Angie waxes lyrical about the shopping dates they will go on when Elsa is older.

The innate contrast between a mother and a father is a beautiful thing to behold. We were designed this way, so there’s no point in fighting it.

It must be acknowledged that we do not live in a perfect world. Divorce, death, and domestic troubles can get in the way of what God and nature intended. For this, too, there is grace—not least in the form of safe father and mother figures who can step in to fill the gap left by such tragedies.

But let not the exception write the rule. The value of getting married before starting a family and then working hard to cultivate a healthy, lifelong marriage is one of the greatest gifts we can ever give our children.

Fathers, whatever your situation this Sunday, please know that you mean more to your child than you will ever comprehend. Your calling is a high one.

And as I often like to remind myself, “the good old days” are happening now, so don’t miss them.

Happy Father’s Day!

– – –

Kurt Mahlburg is an emerging Australian voice on culture and the Christian faith. He has a passion for both the philosophical and the personal, drawing on his background as a graduate architect, a primary school teacher, a missionary, and a young adults pastor. Since 2018, Kurt has been the Research and Features Editor at the Canberra Declaration. He is also a freelance writer and a regular contributor at Mercator, the Spectator Australia, Caldron Pool, and Intellectual Takeout. He is married to Angie, who hails from Milwaukee, Wisconsin.