by Aubrey Gulick

Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster was known for insisting on wearing her traditional habit — even when most of the Oblate Sisters of Providence had adopted more modern garb.

“I am Sister WIL-HEL-MINA,” she would say. “I’ve a HELL of a WILL, and I MEAN it!”

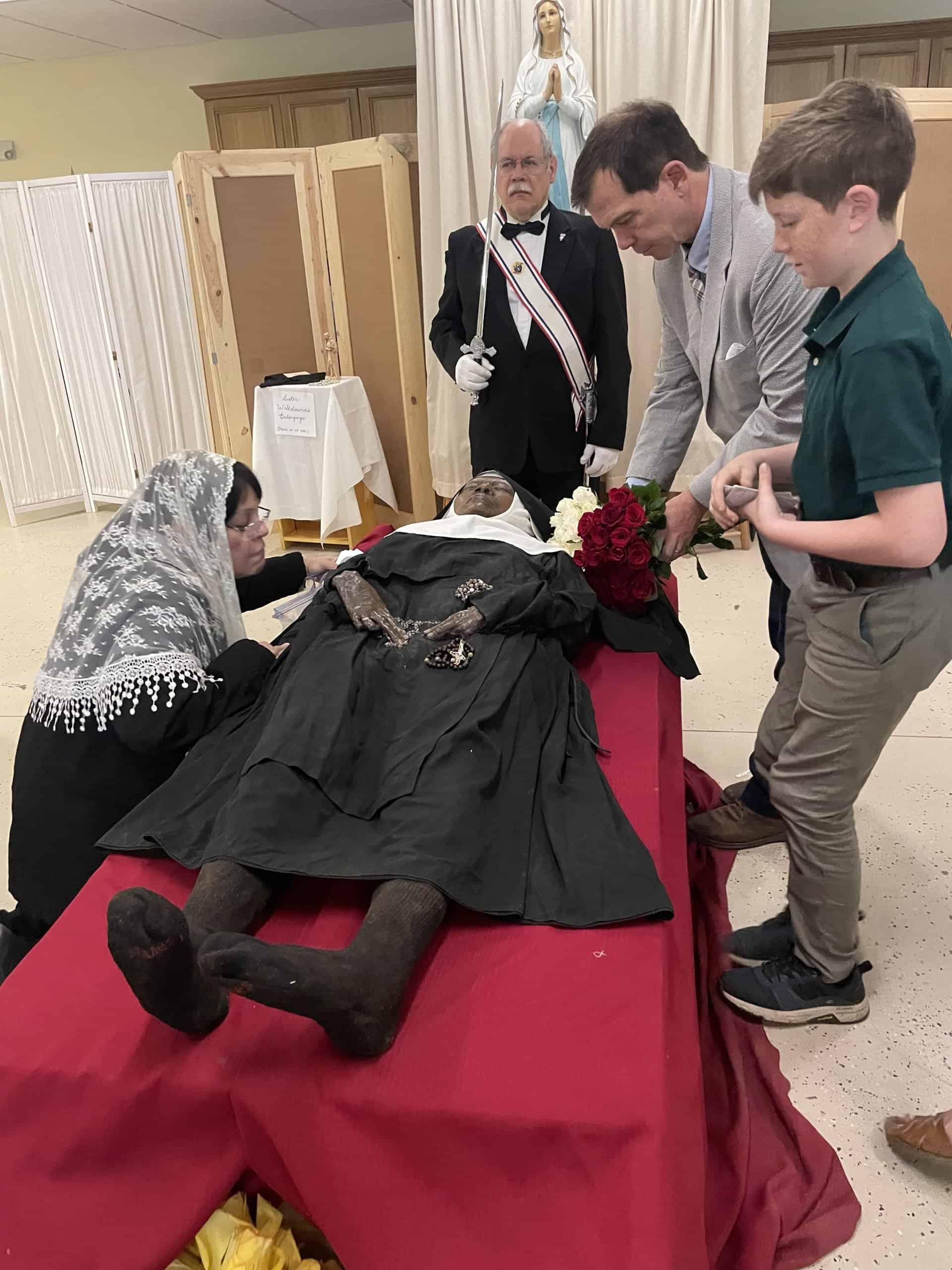

So it’s fitting that when the sisters of the Benedictines of Mary Queen of the Apostles in Gower, Missouri, the order she founded in 1994, exhumed her, they found that her body was completely intact and that her habit was in pristine condition.

If you heard of the Benedictines of Mary Queen of the Apostles before last month, you probably knew them as the “singing nuns,” a moniker they earned after they topped Billboard’s classical music charts.

Until last month, the sisters did not get many visitors, but ever since a private email about Sister Wilhelmina’s incorrupt body leaked to the public, thousands of Americans, Catholic and non-Catholic alike, have made the pilgrimage to Gower, Missouri.

It’s a pilgrimage that seems especially strange in a modern age that encourages skepticism of anything that suggests God’s role in the world.

“You walk in, and you’re thinking: ‘How bizarre, we’re going to be with a dead body that’s been dead for quite some time,’” Karen Hickey, a mom of six from Front Royal, Virginia, told The American Spectator. “I’m not sure if anyone who is alive has ever approached an incorrupt [person] that you’re able to smell and touch and kiss.”

The Sassy Nun

When the Hickey family made the 17-hour trip to Gower, Missouri, at the end of May, it was not their first time. Karen Hickey and her daughters visit annually for retreats. By chance, or perhaps Divine Providence, a friend had recommended that the family ask to meet Sister Wilhelmina (pictured above), then 94 years old, while they were visiting five years ago for the first communion of their youngest son.

“There was a hubbub of activity because it was right after first holy communion,” Karey Hickey said. “Sister Misericordia Scholastica wheeled her into the parlor, and we met her. She was in a wheelchair at the time and was not in the best of health.”

The visit lasted only a few minutes, but the Hickeys were struck by how cheerful the elderly nun was. “She was sassy,” David Hickey remarked.

After Sister Wilhelmina died in 2019, the Hickeys began researching her life.

“Her story is just amazing; if she’s not in heaven, I don’t know who is,” David Hickey said. “This faithful nun for 75 years starts this traditional order in response to her own order modernizing … her personal sanctity seems obvious.”

A Life of Personal Sanctity

Sister Wilhelmina was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on April 13, 1924. By age 13, she knew what she wanted to do when she grew up — so she wrote to a local convent that she intended to become a nun.

At the age of 17, she joined the Oblate Sisters of Providence. Sister Wilhelmina would spend 50 years teaching in Catholic schools around the country and serving as the order’s archivist.

In 1995, at the age of 70, Sister Wilhelmina packed her bags and left the Oblates to start a new order alongside the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter, a group of priests who are devoted to celebrating the Tridentine Latin Mass, in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Sister Wilhelmina moved her order to Gower in 2006, and they began construction on the convent where they live today. She died on May 29, 2019, surrounded by her sisters.

Discovering Her Body

Four years later, at the end of April, the nuns resolved to move her body from the grave in the convent cemetery to the recently completed chapel. When Mother Abbess Cecilia Snell first peered inside the cracked coffin lid, the last thing she expected to see was a human foot encased in a black sock. Upon seeing it, she screamed for joy.

“It was a very different scream than any other scream,” the abbess said in a recent exclusive interview with EWTN News In Depth. “Nothing like seeing a mouse or something. It was just pure joy. ‘I see her foot!’”

The sisters discovered that Sister Wilhelmina’s body and habit, including her eyebrows, eyelashes, Hanes-brand socks, and rosary beads, were remarkably well preserved. However, the coffin’s fabric lining had disintegrated.

“I think everything that was left to us was a sign of her life,” Sister Scholastica said. “Whereas everything pertaining to her death was gone.”

‘Visiting an Old Friend’

Karen Hickey and one of her daughters had just returned from a conference in Kansas City when they heard that the public could visit Sister Wilhelmina’s body. The family got in the car and drove 17 hours back to Gower.

After standing in line for half an hour, the Hickeys were able to approach her body.

“It’s like you’re visiting an old friend. She was just there,” Karen Hickey said. “You’re kneeling down and thinking that she looks like she just went to sleep.”

In a public statement, the sisters clarified that Sister Wilhelmina’s cause for canonization has not yet been opened and that the Catholic Church does not consider incorruptibility to be evidence of sainthood.

“We know … that all things must be subjected to further scrutiny, especially by the competent authorities in the medical field,” the sisters wrote.

Many Catholics have found the event particularly inspiring in the context of recent events, including the Los Angeles Dodgers’ spectacle with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

“God is good all the time, God is always in control, and God has a sense of humor,” Karen Hickey said. “Of all the times in history, this is what we needed; He knew we needed this.”

– – –

Aubrey Gulick is a recent graduate from Hillsdale College and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute Fellow at The American Spectator. When she isn’t writing, Aubrey enjoys long runs, solving rock climbs, and rattling windows with the 32-foot pipes on the organ. Follow her on Twitter @AubGulick.

Photo “Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster” by Benedictines of Mary Queen of Apostles.