The State of Arizona Elections Procedures Manual (EPM) for 2019 that prescribes the Secretary of State’s rules for running an election has no provision for qualifying or certifying the equipment a third-party vendor uses for ballot signature verification in Maricopa County.

According to state law A.R.S. 16-452, the secretary of state is responsible for prescribing in an official instructions and procedures manual the rules to achieve and maintain the maximum degree of correctness, impartiality, uniformity and efficiency on the procedures for early voting and voting as well as producing, distributing, collecting, county, tabulating and storing ballots.

In summary, the EPM is intended to help ensure election practices are consistent and efficient throughout the state and has the force of law.

The secretary of state is required, in the same section of the statute, to submit the manual to the governor and attorney general for their approval no later than October 1 of each odd-numbered year immediately preceding the general election so that it can be issued by December 31 of that same year.

Current Secretary of State Katie Hobbs didn’t submit the 2019 version of the EPM to Governor Doug Ducey until December 19, 2019, and Attorney General Mark Brnovich until December 18, 2019. Both approvals were provided to Hobbs the day following receipt by the respective offices.

Hobbs met the October 1 deadline for submission of the 2021 Elections Procedure Manual to the governor and attorney general, but Brnovich informed Hobbs on December 10, 2021, that it must be changed in order to comply with state law.

Neither the 2019 nor the 2021, though not approved and in effect, versions of the EPM address the certification and use of any equipment other than that of the voting system.

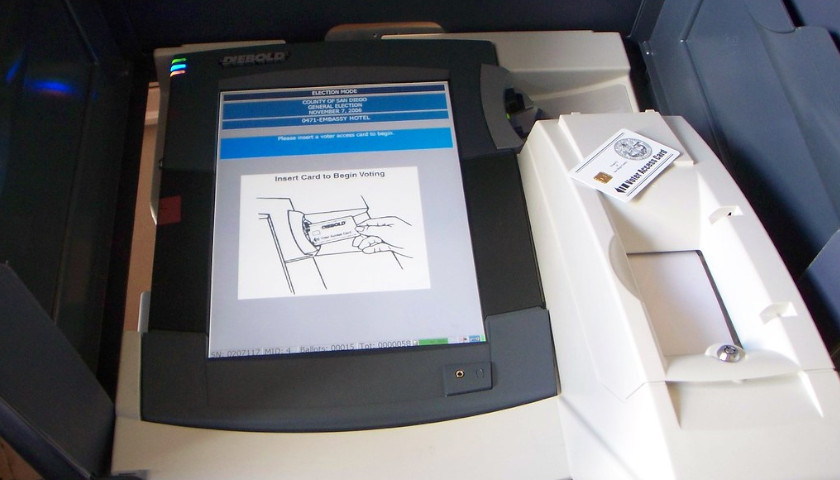

The equipment of the voting system is defined as the total combination of mechanical, electromechanical or electronic equipment including software, firmware and documentation required to program, control and support the equipment used to define ballots, cast and count votes, report or display election results and maintain and produce any audit trail information.

The voting system, according to the last approved EPM from 2019, consists of the central count equipment, precinct voting equipment, accessible voting equipment and the election management system used to tabulate ballots.

Chapter 4 titled Voting Equipment is the only one of the 17 chapters in the 2019 EPM that addresses equipment. However, the process for certification, logic and accuracy testing and security is limited to the defined voting system equipment.

Meanwhile, as the lawsuit filed by Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake exposed and the Maricopa County Elections Department 2022 Elections Plan for the August primary and November general election confirms, third-party vendor Runbeck Election Services uses a combination of equipment to scan the affidavit envelope to capture an image of the voter’s signature.

Once the images of signatures are captured via a scan, Runbeck places the images into an automated batch system for the Maricopa County elections department staff to review.

Since a match in signatures between the affidavit and the voter’s registration record, as determined by election workers in the office of County Recorder Stephen Richer is required for the ballot to be counted, it is “currently the most important election integrity measure when it comes to early ballots,” Brnovich has stated.

The Ninth Circuit acknowledged in Arizona Democratic Party v. Hobbs that “Arizona requires early voters to return their ballots along with a signed ballot affidavit in order to guard against voter fraud.”

In the November 8 general election, Maricopa County reported that 1,311,734 of the 1,562,758 or nearly 84 percent of all ballots cast were early votes for which signature matching must be completed.

The 2019 EPM specifies logic and accuracy testing for optical and digital scan voting equipment. While the voting equipment uniquely must attribute votes correctly, some of the other required testing could be applied to the signature scanning process. For example, such testing could include as a minimum, precision in the quality of the scanned signature, a warning to the operator of a missed or duplicated physical or digital signature and confirmation that all scanned signatures ended up in the automated batch system.

Once the county recorder’s office reviews the signatures sent from Runbeck and determines whether the affidavit has a good signature, no signature, questionable signature, needs a packet or any other determination, the dispositions are sent to Runbeck.

Runbeck then sorts the ballot packets based on the recorder’s office dispositions and puts each disposition type into smaller physical batches of approximately 250 pieces per batch.

Further testing could be performed on the transfer of dispositions from the recorder’s office to Runbeck to ensure that the vendor receives accurate information for the essential sorting function.

A final check, unrelated to equipment, should verify that the batches received at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center (MCTEC) facility from Runbeck correspond to the dispositions from the recorder’s office.

Even if the state were to have a procedure to qualify the signature scanning equipment used by Runbeck and Maricopa County, that would still leave a gaping hole in the qualification of the overall process of ballot handling and the complex chain of custody associated with mail-in ballots.

The fact is the EPM devotes less than 25 pages to ensuring the accuracy of the voting equipment, even though Arizona relies almost exclusively on machines for elections, and does not seem to even contemplate the use of equipment for the critical signature verification process.

– – –

Laura Baigert is a senior reporter at The Star News Network, where she covers stories for The Arizona Sun Times and The Tennessee Star.

Photo “Poll Worker Checking Signature” by Phil Roeder. CC BY 2.0.

Come back when somebody’s butt gets kicked for the cheating…..mainly Hobbs.

A bunch of damn fools in Cochise county voted Fascist anti-American bastards into control of our once free state. Now, we have gutless wonders saying it was wrong. What in the name of God ever became of actually fighting for our country? My generation did and sacrificed our teen aged years to help defend our freedom. Would we do it again? Your damned right we would because we believed in our free country, and what’s left of used still do and would if possible. And many did much more than simply giving their time and years. For what? So a bunch of Fascist bastards can take over our country without taking a shot?

this should be settled easily and quickly.florida did it ,other states have done it.

No election should take weeks after voting is over.

a clean vote and verification should be possible if the state really wants it.

get it done for integrity in this state.

David H Pfeifer, you got that right. Way back in the early 1930s my mother worked on election boards. The poles closed, they sent the locked ballot box in, the voted were counted and the next morning we knew who had won. There were no cellphones, computers and phones were for the most part on party lines. The only reason elections take so long now is FRAUD!

This is why hobbs had no business holding onto the Secretary of State position while running for governor at the same time. She should have recused herself as her opponent Kari Lake suggested so there would be no appearance of impropriety. But now, it just looks like she arranged certain malfunctioning voting machines in Republican dominated districts. Not a cool look, katie, not a good look at all.

Thank you Kari Lake.

Bruce Wales, perhaps we should ALL rise up and DEMAND A RECOUNT. Personally, though I’m not what would be called a fan of Karry Lake, I think she got thoroughly screwed in this election.

No one is ever held accountable for these critical responsibilities. The Secretary of State should have recused herself from being involved and should have executed her duties of making the machines were working properly. Another example of voter cheating extremely possible. What will the Attorney General do to correct these errors?

There is first-rate system engineering talent available at General Dynamics (Scottsdale) and other high-tech companies in the area — put out an ‘RFP’ to this company and others to design whatever election systems we need, work carefully through the requirements, and award at least two contracts for election integrity systems. Use American companies only, make careful pre-testing with partisan observers part of the contract, run multiple systems in parallel, include bonuses for early delivery and 6-sigma quality verification, and put this nonsense behind us!

If the signatures aren’t verified and the chain of custody is not monitored. Anything could happen to the ballots, not counted, over or double counted, incorrect vote tabulation. Basically, a chaotic free for all with no monitored checks and balances

To rerun 2020

Election integrity is what makes America great but hunger for power makes our people corrupt. SAVE AMERICA